Collector's Outlook: Single-sided K&E rules

Note: Suggested prices are for slide with case on eBay. Any extras, especially those considered complete, with box and documentation, can double these prices.

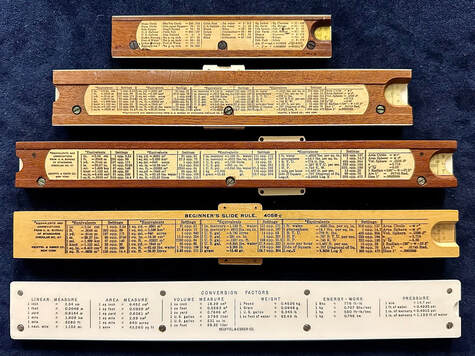

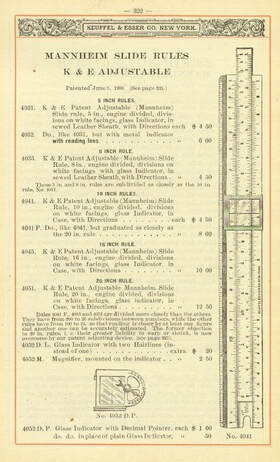

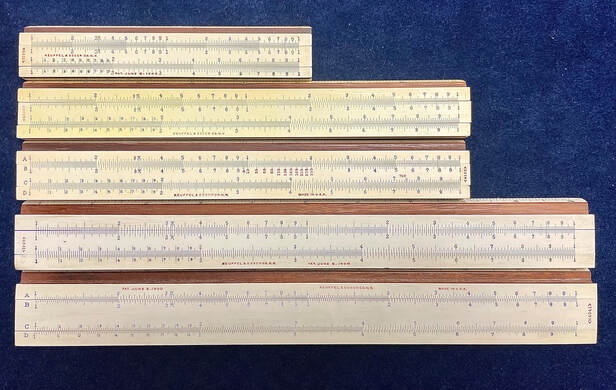

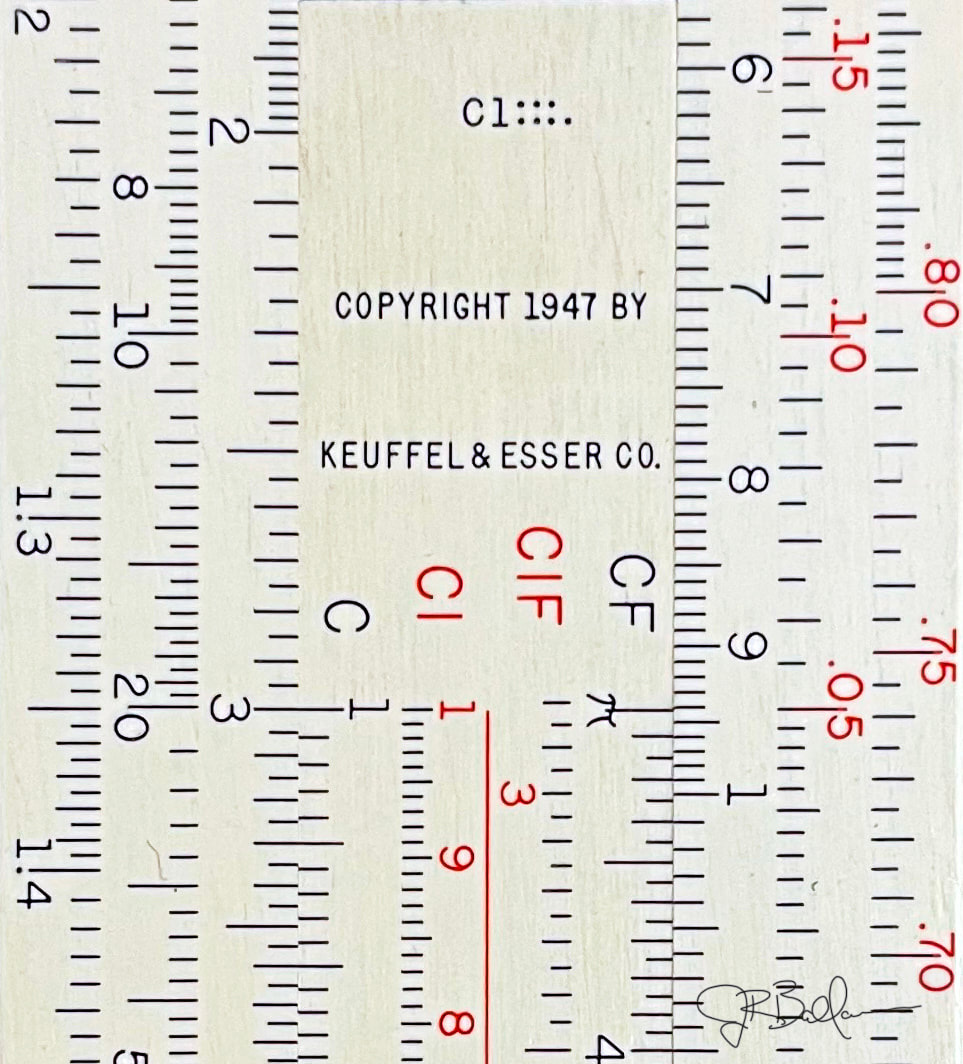

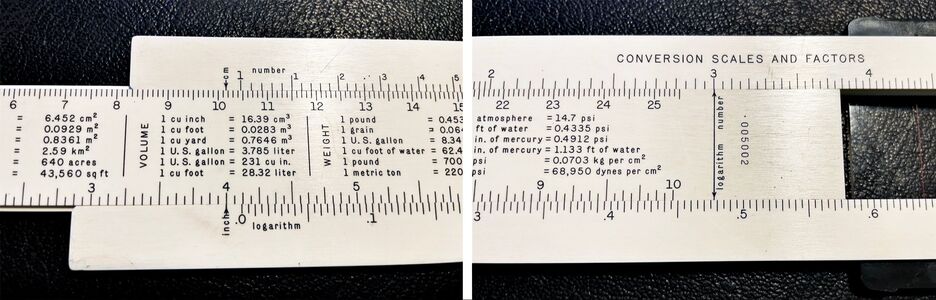

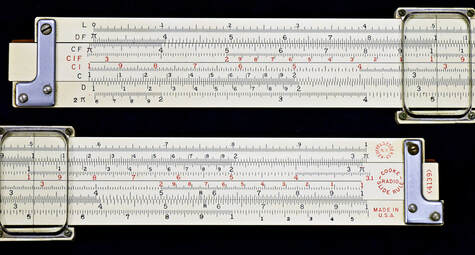

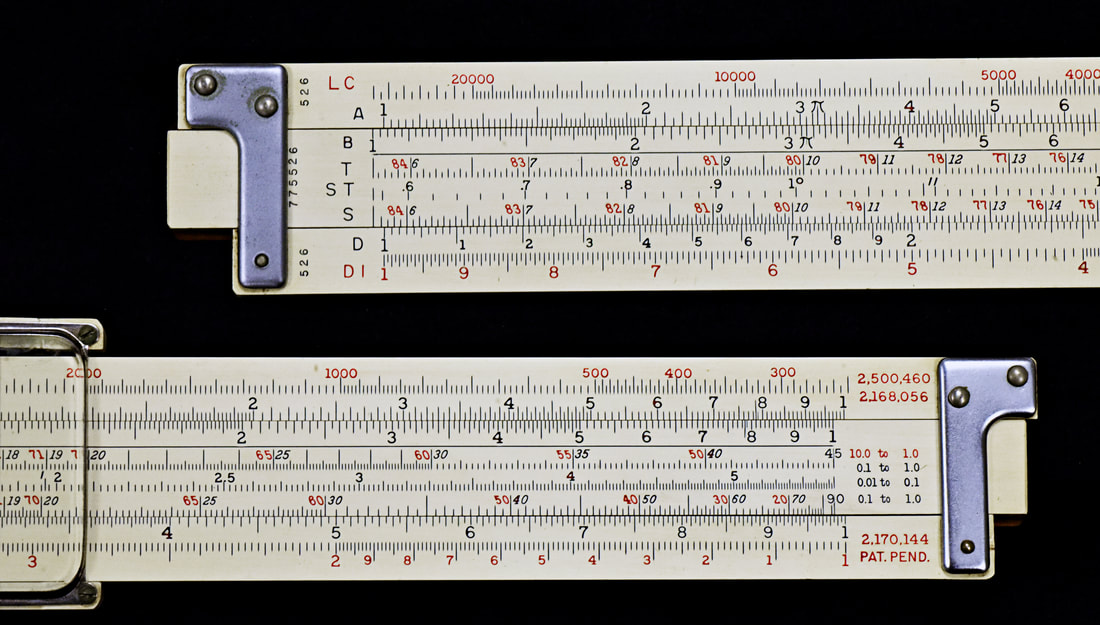

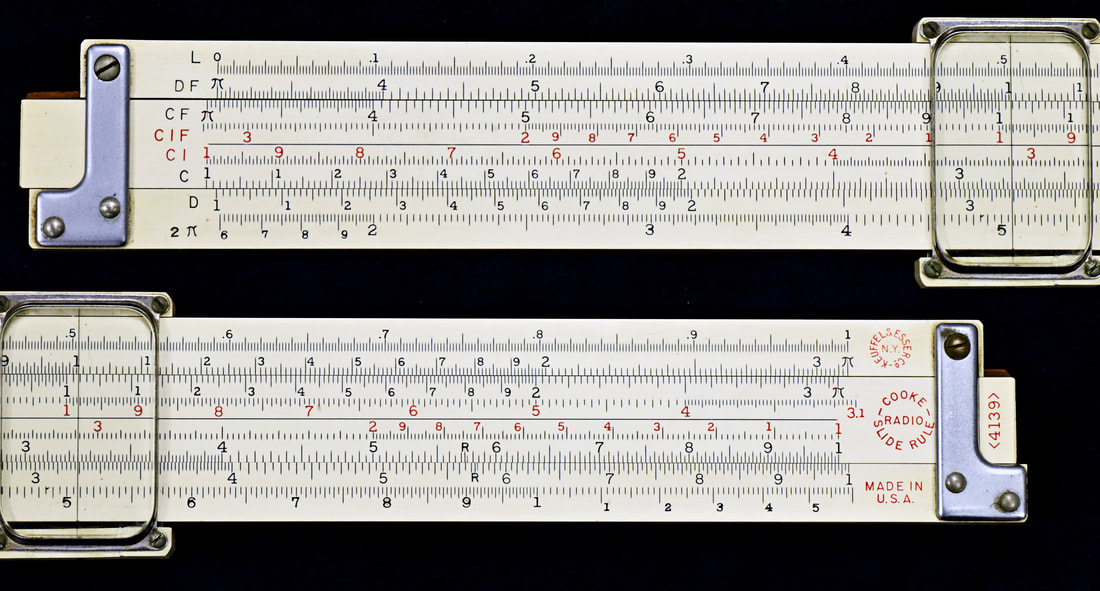

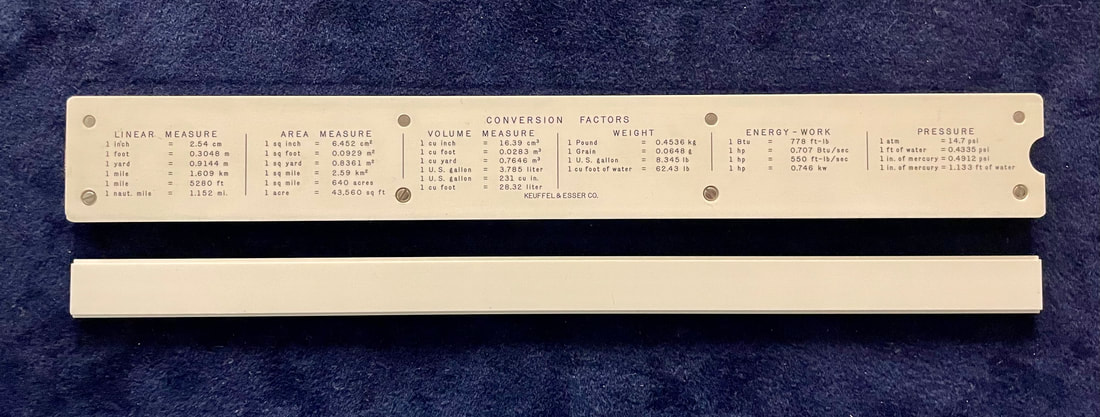

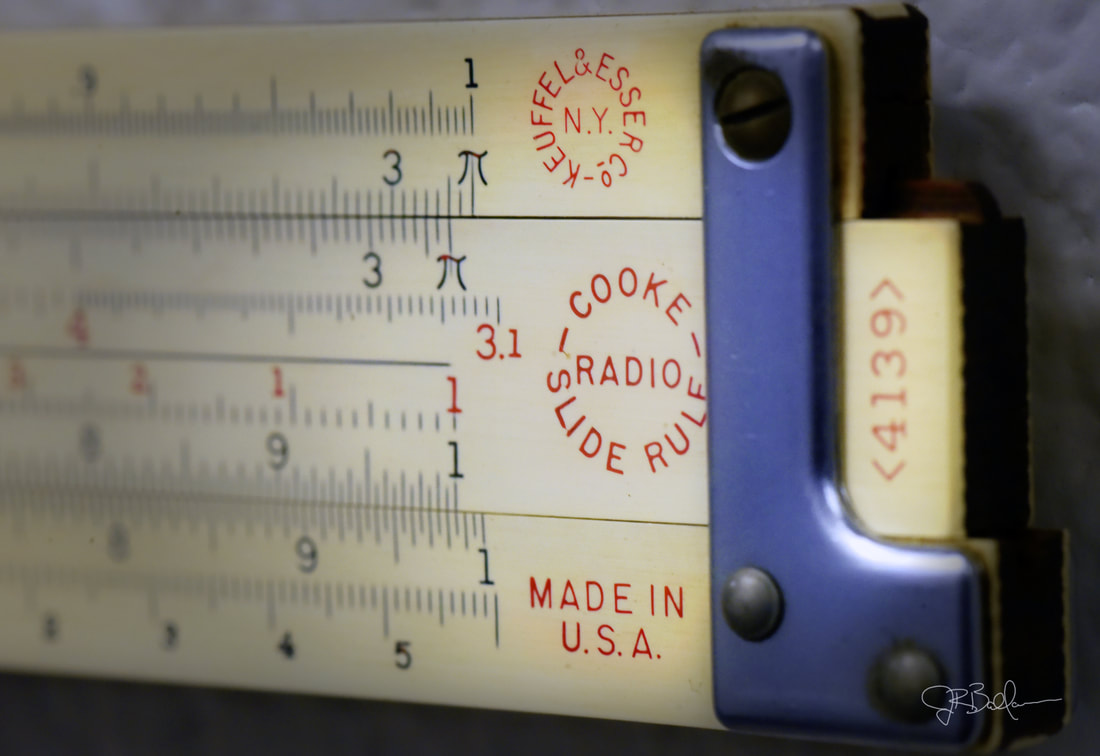

Single-sided K&E rules are easily collectible, if by "collectible" we mean easily and cheaply found. The basic student rules of the 4058 series are abundant on used markets between $10 and $20 respectively for the full-scale 10" rule. The same can also be said of the 4053 Polyphase series. The 8" and 20" versions do carry a higher price, but can typically be found in the $30 to $60 range depending on condition and completeness.

The special versions of the Beginner's rule, Models 4059, 4058D, and 8858 Special War Time rule are all very rare, appearing maybe every other year on eBay. Prices for the 4059 and 4058D are as cheap as the normal 4058 rules, likely because nobody recognizes them when they come up and aren't truly collectible. On the other hand, the Model 8858 with its special war time packaging is more collectible, likely going for $50 to $100 if one were to come up again. It has been quite some time that this has happened for any of them.

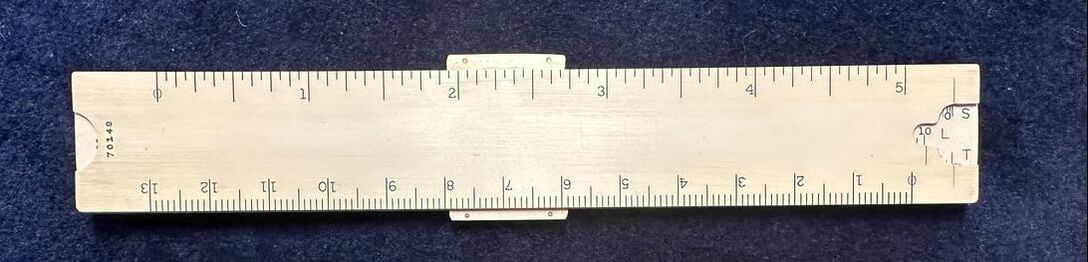

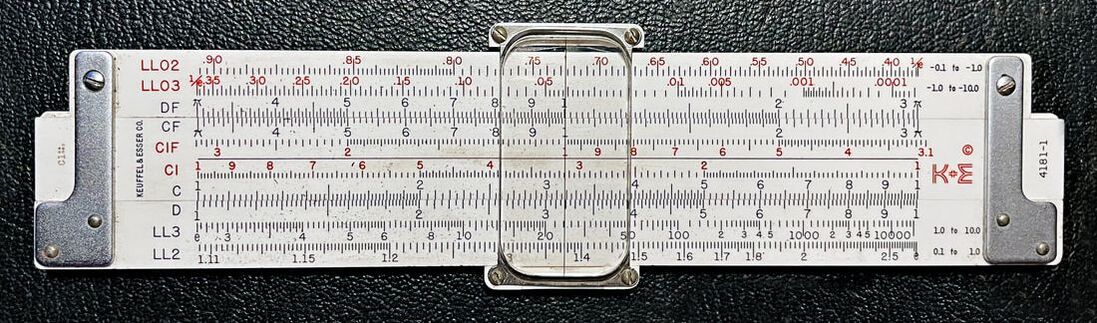

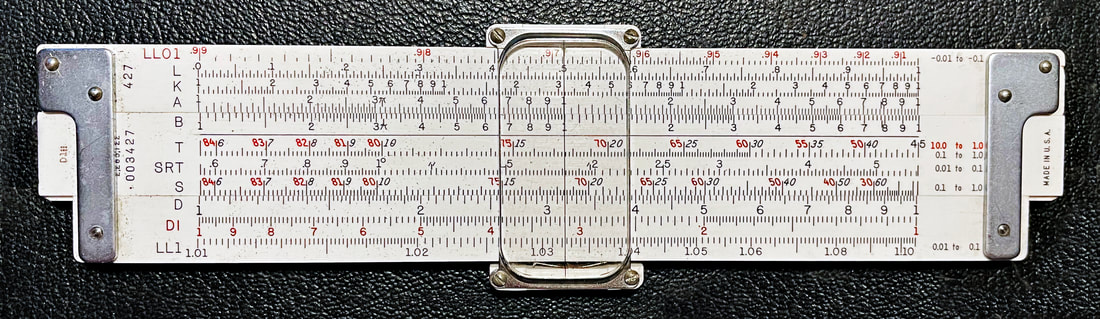

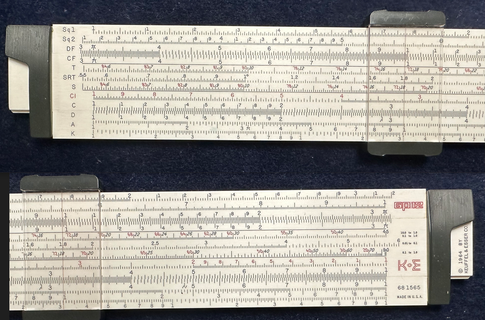

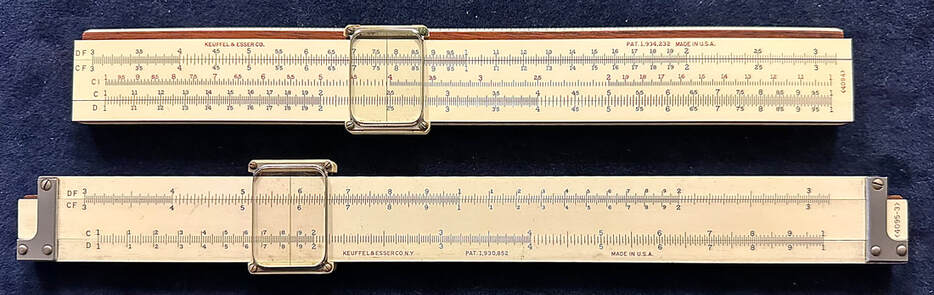

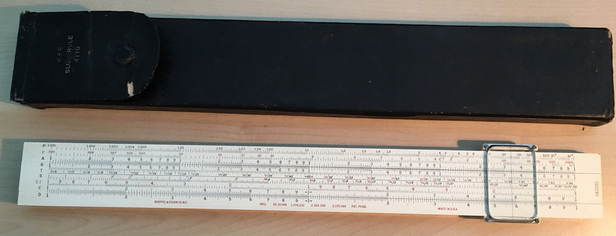

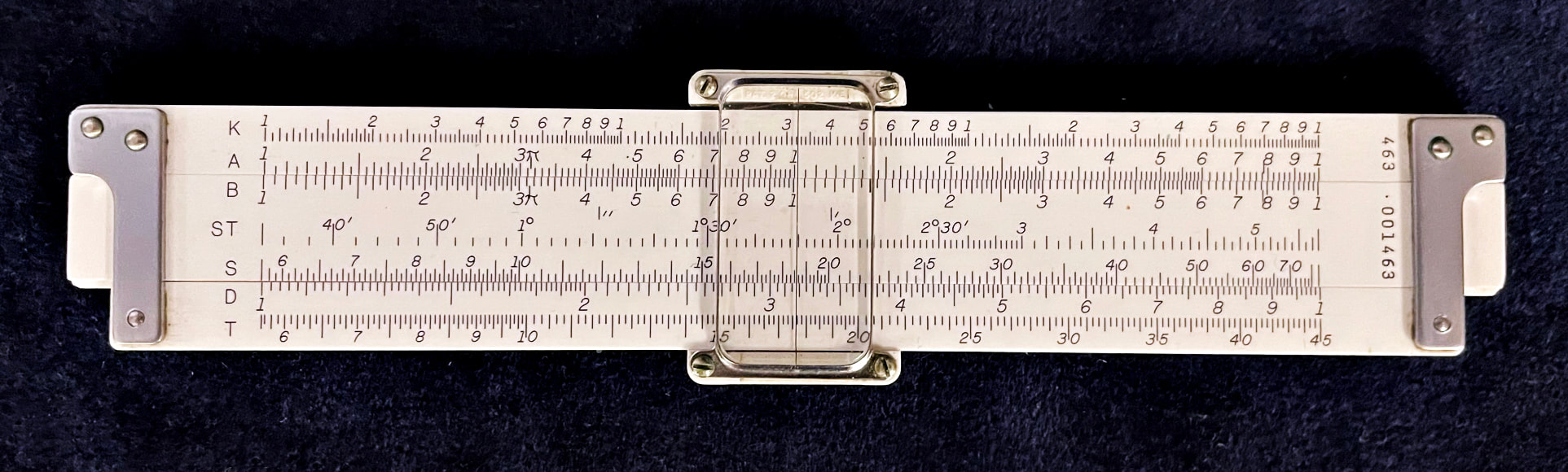

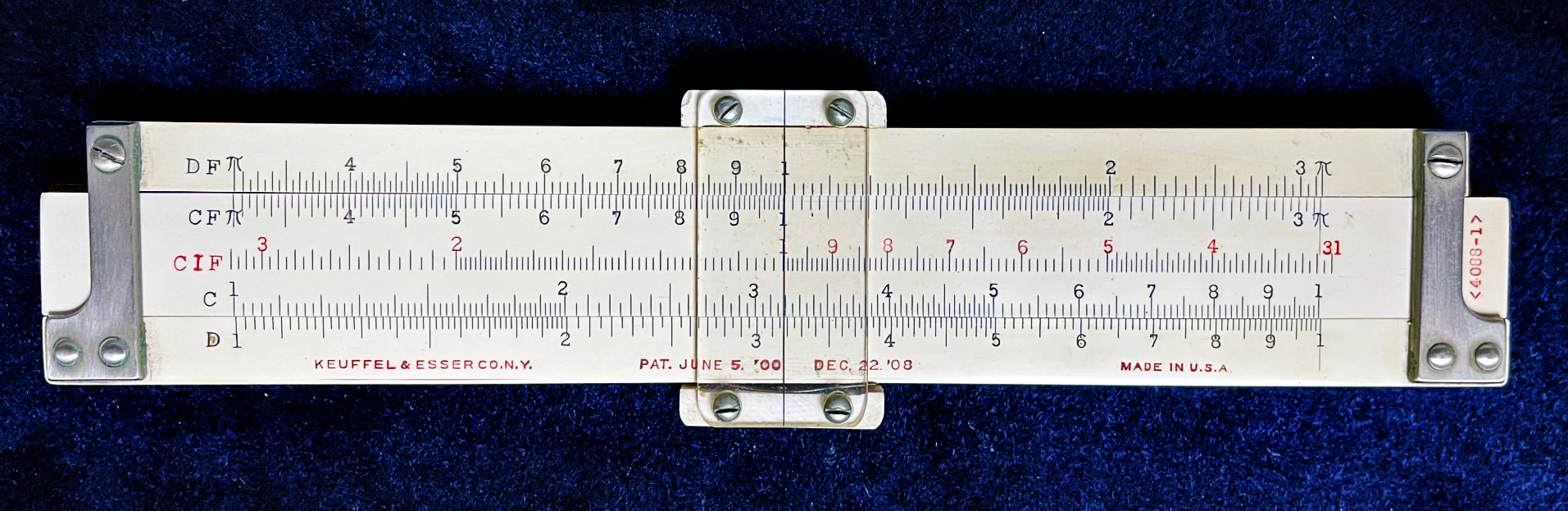

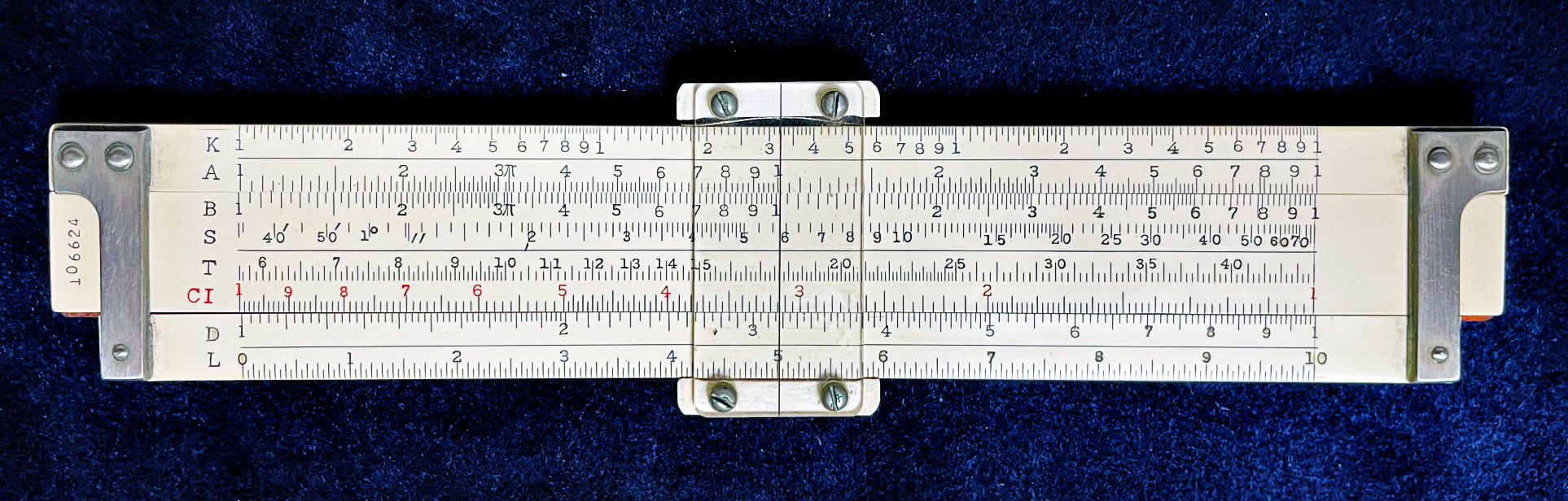

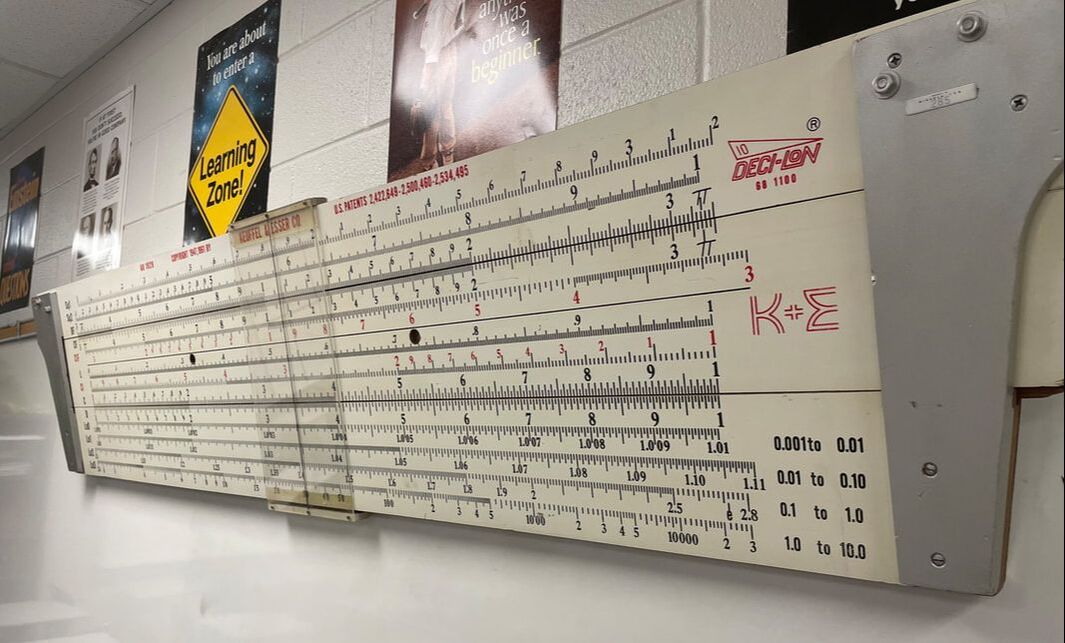

The 4041 series is also quite common, likely $15 to $20 for a rule in good condition. The variations of this rule are where they become much more desirable. The 5" 4031 and 8" 4035 are difficult to find. The 4031 model comes up on eBay maybe once a month, selling for around $40 on average. The 4035, maybe once per year for a similar price. The original 4040 version in this series, that with the brass cursor, only had a run of 5 production years, and thus it's quite rare. Only two samples have been sold on eBay over the last 23 years, averaging $273. A sample of the 16" 4045 and 20" 4051 will come up for sale every other month or so, with an average price of ~$50. Of course there's often another one posted for maybe 3 times that amount that remains there forever.

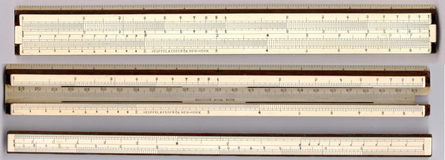

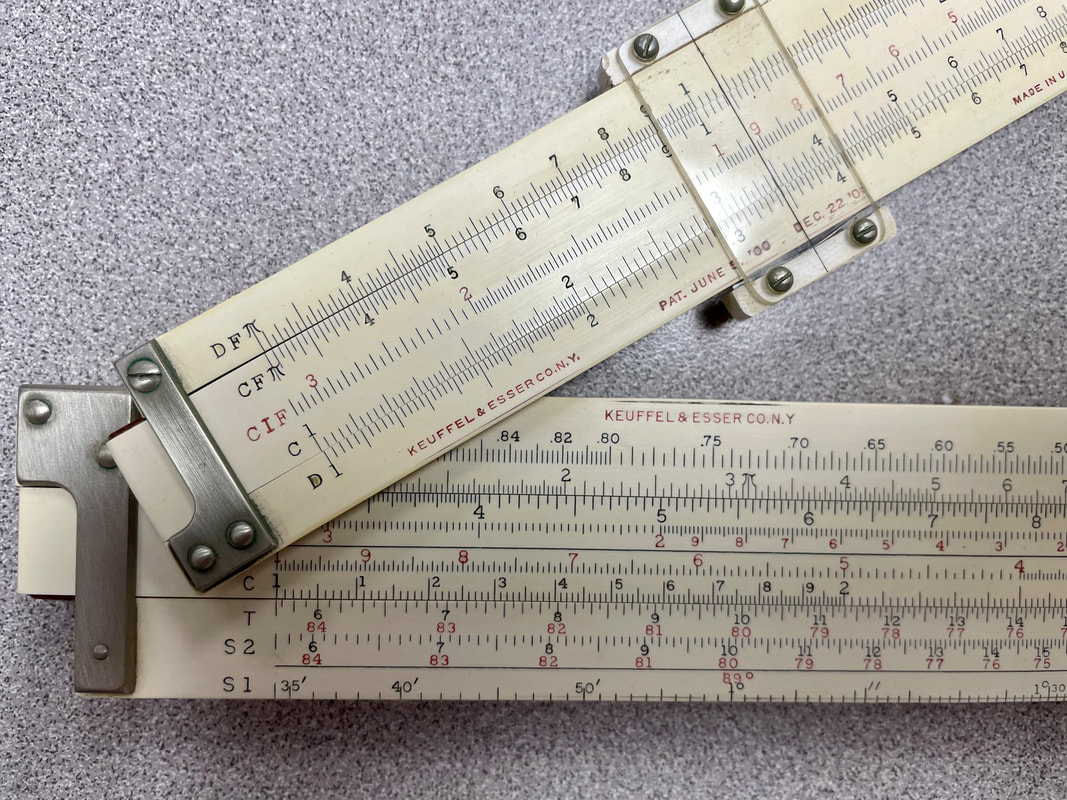

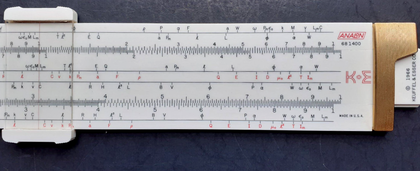

Highly desirable is the "F" or "fine-scale" version of the 4041 and 4053 slide rules. They come up maybe once or twice a year with an average selling price of perhaps $100.

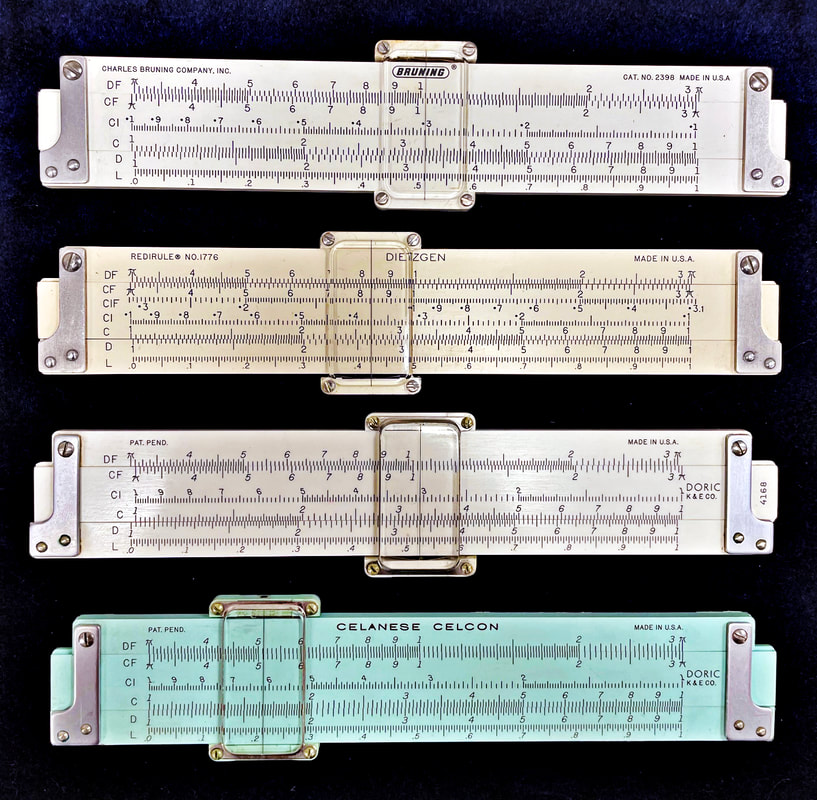

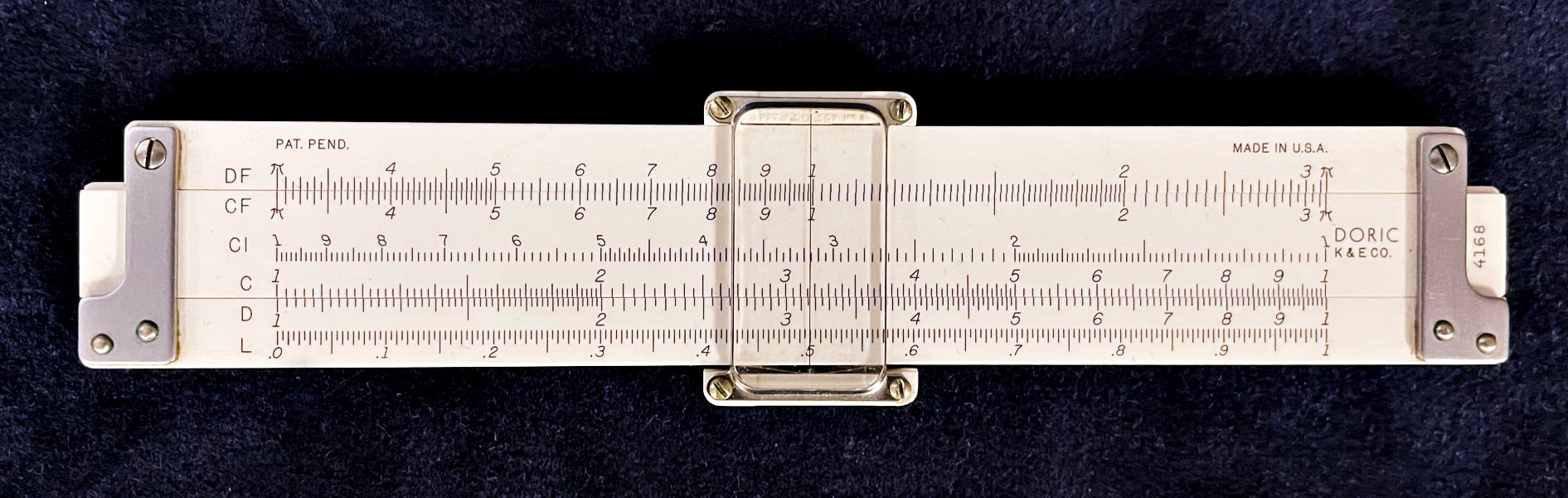

Others that are moderately collectible are the 4054/4055/4056 "Favorite" series of rules, which are found easily on eBay for maybe $20. The exception is the original boxwood version of the 4054 and 4056 rules, which are very difficult to find, as most in the wild are the later mahogany versions. Very few have come up on eBay over the last couple of decades, though prices are less than $100 for the 4054 and $20 for the 4056 when they do.

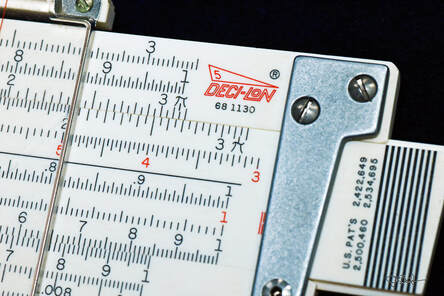

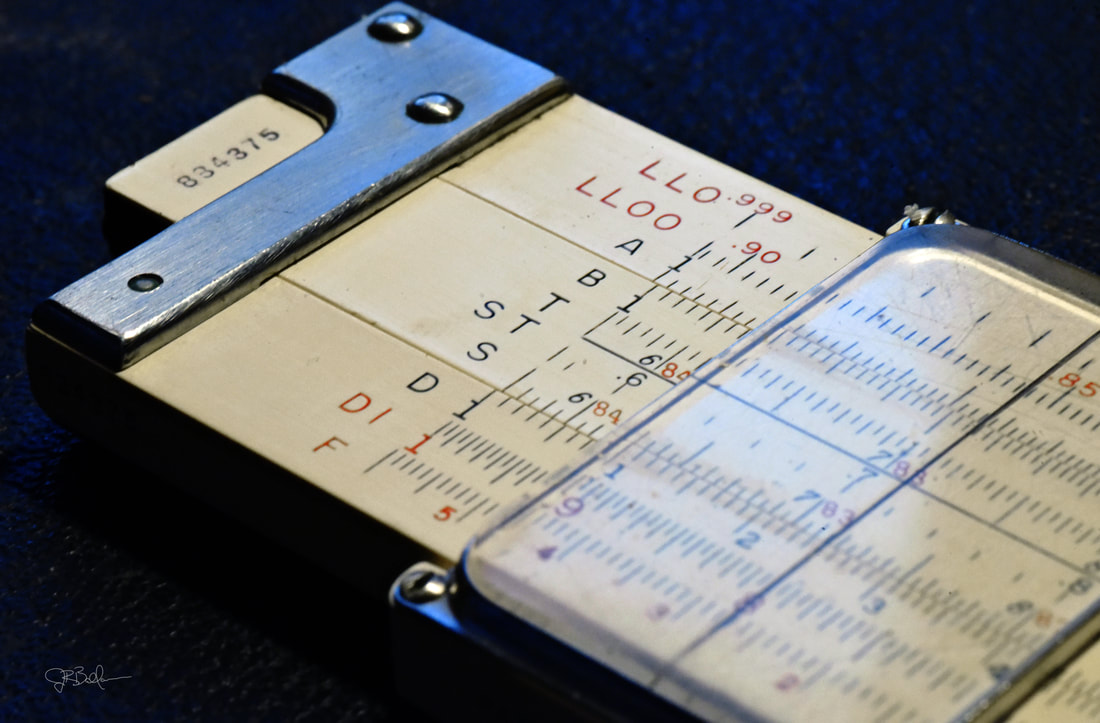

Any of the Ever-There Pocket rules, as well as most of the more modern pocket rules made of the better plastics come up very frequently on eBay and can be had for around $15 to $20 or so.

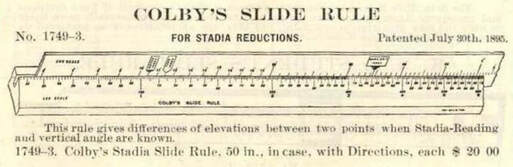

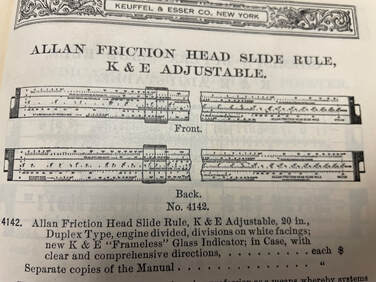

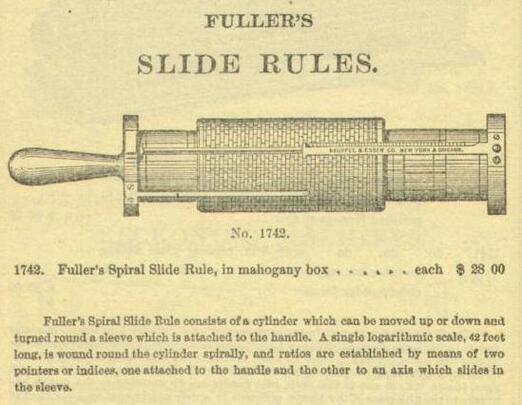

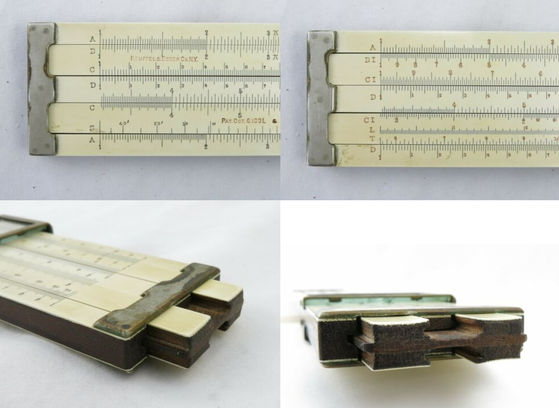

Anything from the 19th century is basically a unicorn. Only a couple of 1746 samples have come up on eBay over the last 23 years, selling for around $1000 each. The early 1749-1 Beginner's rule has seen one sample sold on eBay for nearly $500. The so called "American" slide rule, in the box, exists in very few collections. This can cost perhaps $300 to $500.

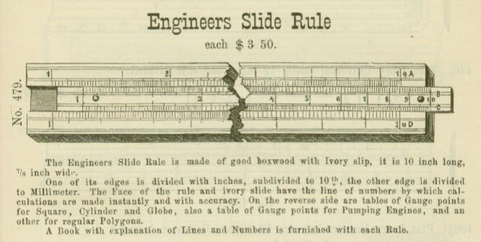

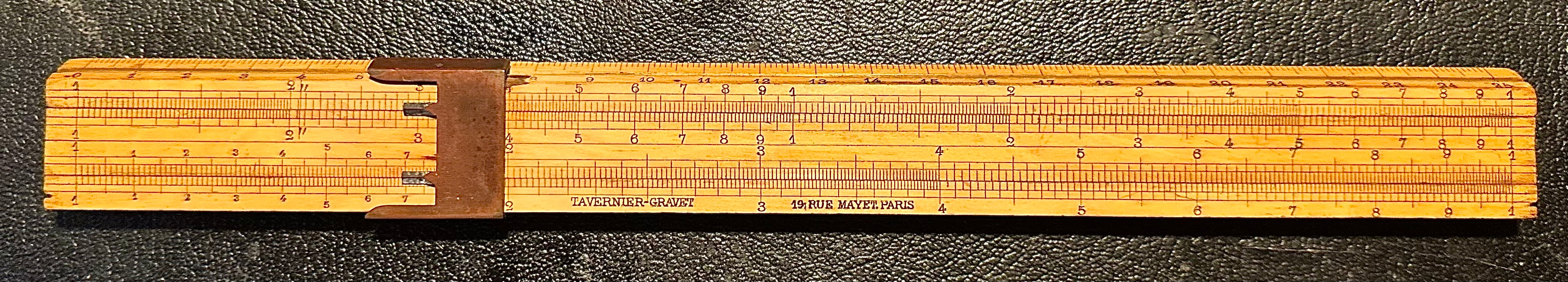

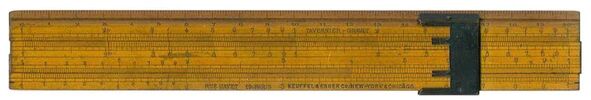

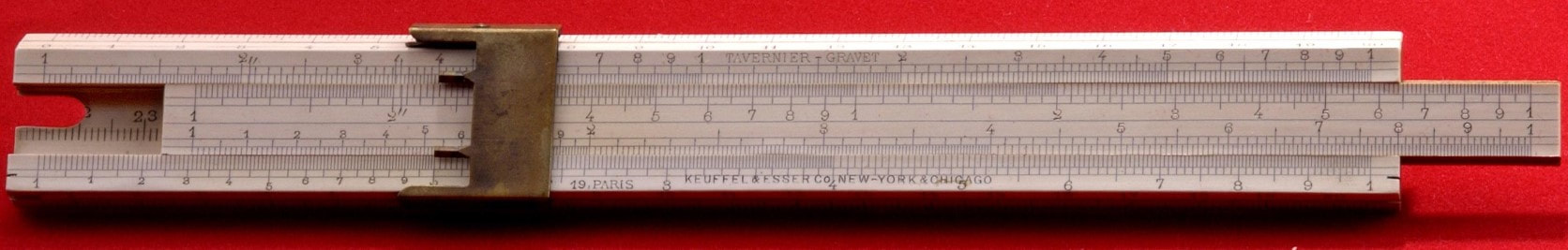

I never seen a Model 479, nor it seems has anybody else, though I would speculate that these rules were those imported from Tavernier-Gravet, lacking the model number which could have been known as the Model 479.

Single-sided K&E rules are easily collectible, if by "collectible" we mean easily and cheaply found. The basic student rules of the 4058 series are abundant on used markets between $10 and $20 respectively for the full-scale 10" rule. The same can also be said of the 4053 Polyphase series. The 8" and 20" versions do carry a higher price, but can typically be found in the $30 to $60 range depending on condition and completeness.

The special versions of the Beginner's rule, Models 4059, 4058D, and 8858 Special War Time rule are all very rare, appearing maybe every other year on eBay. Prices for the 4059 and 4058D are as cheap as the normal 4058 rules, likely because nobody recognizes them when they come up and aren't truly collectible. On the other hand, the Model 8858 with its special war time packaging is more collectible, likely going for $50 to $100 if one were to come up again. It has been quite some time that this has happened for any of them.

The 4041 series is also quite common, likely $15 to $20 for a rule in good condition. The variations of this rule are where they become much more desirable. The 5" 4031 and 8" 4035 are difficult to find. The 4031 model comes up on eBay maybe once a month, selling for around $40 on average. The 4035, maybe once per year for a similar price. The original 4040 version in this series, that with the brass cursor, only had a run of 5 production years, and thus it's quite rare. Only two samples have been sold on eBay over the last 23 years, averaging $273. A sample of the 16" 4045 and 20" 4051 will come up for sale every other month or so, with an average price of ~$50. Of course there's often another one posted for maybe 3 times that amount that remains there forever.

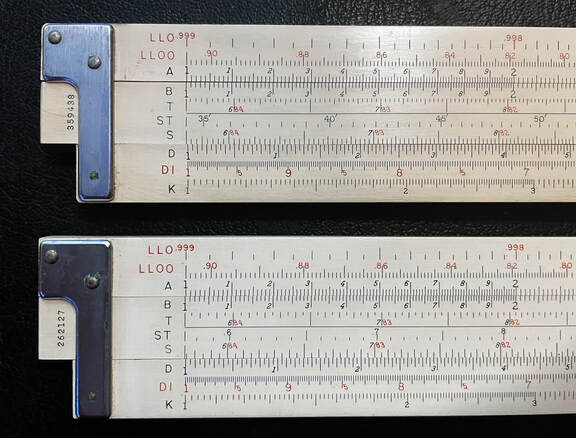

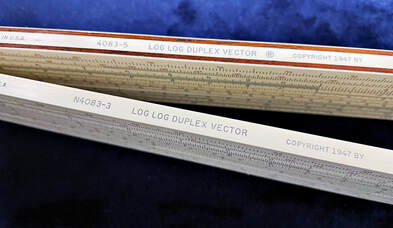

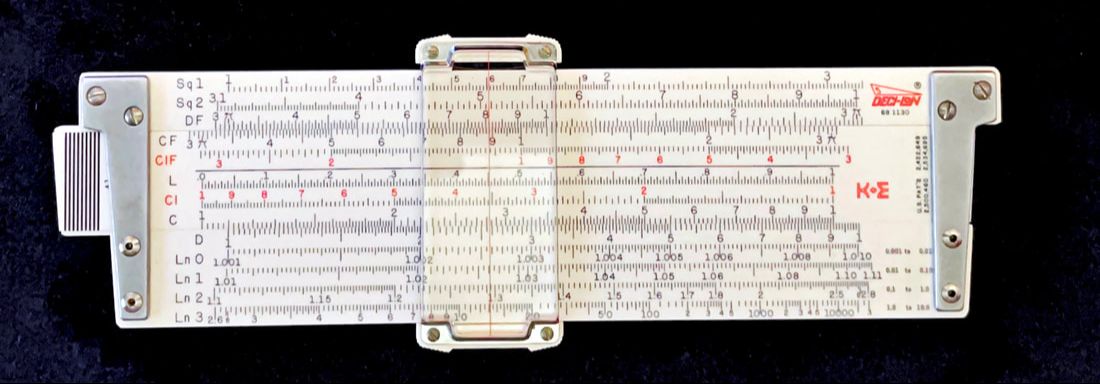

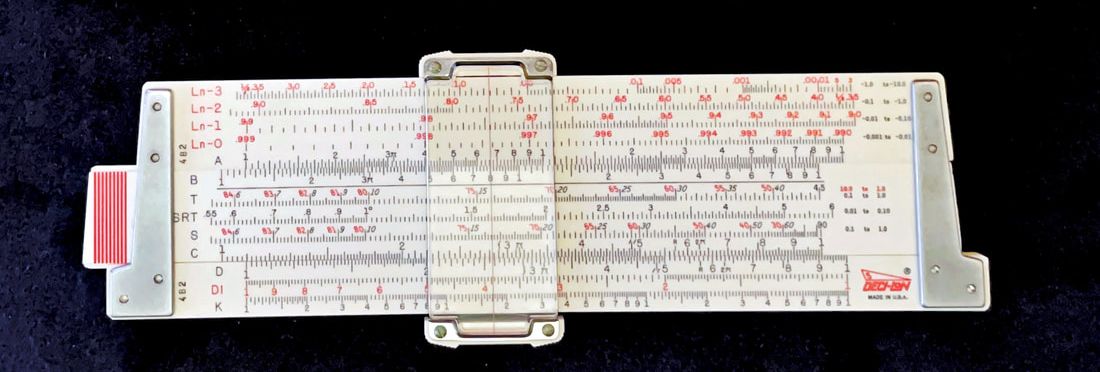

Highly desirable is the "F" or "fine-scale" version of the 4041 and 4053 slide rules. They come up maybe once or twice a year with an average selling price of perhaps $100.

Others that are moderately collectible are the 4054/4055/4056 "Favorite" series of rules, which are found easily on eBay for maybe $20. The exception is the original boxwood version of the 4054 and 4056 rules, which are very difficult to find, as most in the wild are the later mahogany versions. Very few have come up on eBay over the last couple of decades, though prices are less than $100 for the 4054 and $20 for the 4056 when they do.

Any of the Ever-There Pocket rules, as well as most of the more modern pocket rules made of the better plastics come up very frequently on eBay and can be had for around $15 to $20 or so.

Anything from the 19th century is basically a unicorn. Only a couple of 1746 samples have come up on eBay over the last 23 years, selling for around $1000 each. The early 1749-1 Beginner's rule has seen one sample sold on eBay for nearly $500. The so called "American" slide rule, in the box, exists in very few collections. This can cost perhaps $300 to $500.

I never seen a Model 479, nor it seems has anybody else, though I would speculate that these rules were those imported from Tavernier-Gravet, lacking the model number which could have been known as the Model 479.