How to Learn Astrophotography

|

FOREWORD

You will not learn astrophotography over night. You will not be able to read a single article, or even a single book, and think that you can accomplish some of what you see at All About Astro. On the contrary, one article will be quite enough to inform you just how much education about the hobby you LACK; how much there is to learn. Complicating the matter is the Internet. Yes, all you need to learn imaging is on the Internet. It's all there. GO! Where to start? For this reason, having a plan is important. This article, in addition to suggested resources, will outline a plan or approach to your learning. Some of you likely lack a complete clue about what it is that an astroimager actually does...so we will also illustrate a picture of what it's like to be an imager. What is involved with a typical night under the stars? What types of skills do we need to process our images? |

Jumping in with the articles at

|

A PERFECT NIGHT...

The night of an astroimager starts with hopeful enthusiasm. Last night, after all, was a washout. Tonight is a little windy, but that's not an ender, like so much of the weather. Hopefully, the wind doesn't pick up any more, since last month you had much of your "data" ruined by the wind-induced vibrations to your mount. That's why, tonight, you've chosen to shoot with your smaller refractor. Shorter focal lengths means more room for error...so let the wind blow a little.

Setup begins after dinner - a window of 90 minutes of remaining daylight to make sure everything is ready by dusk. First thing you do is put up your small table and the second thing you do is pop open a beer to place on the table...because that's important..

Then, you pull out your big tripod for the "mount," sticking one of the three legs in the general direction of "north." Close enough is all that matters for now, since you'll need to see Polaris before you can actually "polar align" the mount.

Next is your equatorial mount "head". Heavy, weighing about 40 lbs. itself, you are thankful that you ditched the $400 case you normally keep it in...it's such a pain trying to grab it out of the foam padded case! From the back of the SUV to the tripod, you strain to lift up the GEM (German Equatorial Mount), spinning it around toward the northern-placed leg prior to attaching the bolts to connect the two.

Counterweights are next. You brought only one to this dark sky site since your small refractor only needs one. It slides on and you bind it to the counterweight shaft with no real care about where - you'll balance the mount later. Oh, but don't forget the stop that screws into the end of the counterweight shaft. You remember very well the time you forgot the stop and a 12 lbs. counterweight slammed into your foot!

You slide the Losmandy rail containing the telescope's rings into the mount's saddle and lock it down. You open the rings, insert the telescope, and lock down the rings. Again, not caring about actual position.

Then it's the finderscope, guidescope, camera adapters, and two separate cameras - your imaging camera which connects to your small refractor and a "guide" camera that goes with the guidescope.

Cables are next, which means out come the laptop PC. USB cables, one each for the mount, imaging camera, and guide camera are run to a USB hub stuck with double-sided tape to that Losmandy rail. Then, a long USB cable goes from hub to laptop. You also run a separate serial cable from your guide-camera to the mount. Power for the mount and both cameras goes to a DIY terminal strip also mounted at the rail, and a power cable connects the strip to a large DC 12v battery. The battery will power all your gear for the duration of the night. You are ingenious!

You tidy up the cables a little bit with zip-ties to keep them from hanging on stuff. And then you release the mounts RA lock to begin balancing the mount. Holding the counterweight shaft to keep it the scope from flying towards the ground, you loosen the counterweight and slide it lower, intermittently locking it in place to see if it perfectly balances out the small, but surprisingly heavy refractor, locking the mount when you achieve balance. You then repeat in the DEC axis, sliding the Losmandy rail in the saddle until you are convinced it will not spin out of control if you let go.

You power up all the hardware, including the laptop, equipped with Windows 7 (because 10 might not work yet with your drivers and you hated 8). When convinced that everything is working, you start-up your chosen planetarium software, TheSkyX, and you wait for the excitement to begin.

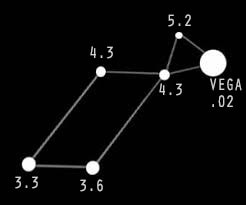

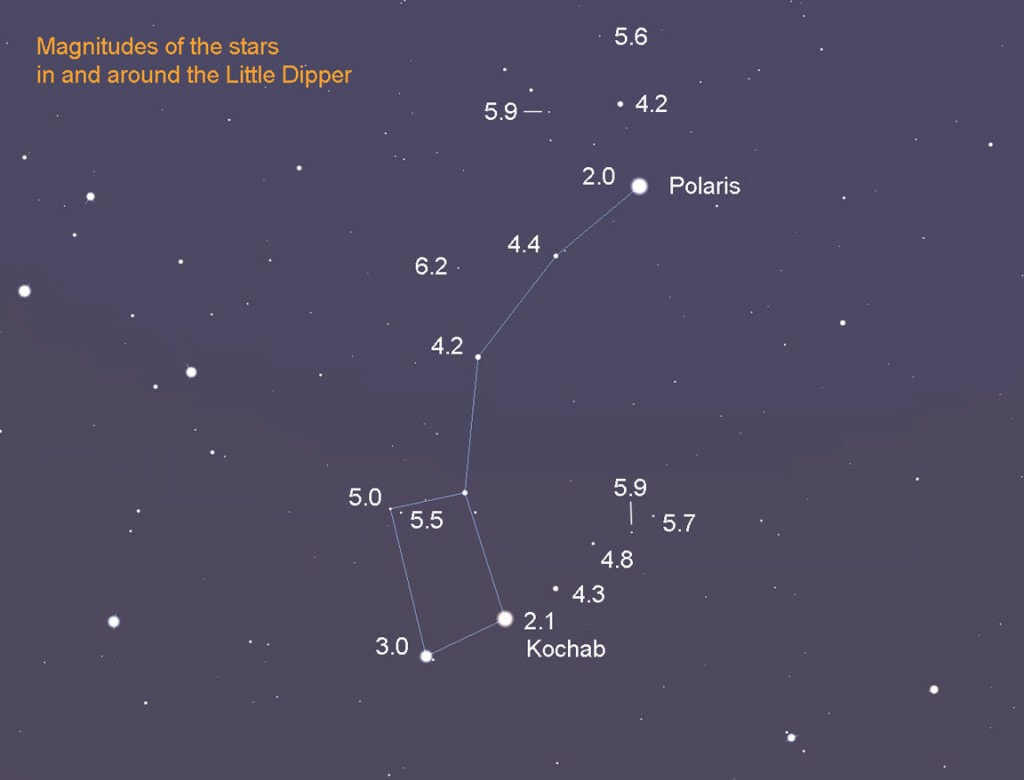

"Polar alignment" begins the moment you can see Polaris, since now you can use your polar alignment scope. Turns out you were remarkably close to it when you first plopped down the mount...you are getting good at this stuff! With allen wrench in hand, you flip on the illuminated polar reticle and compare it to the one shown on an app you've brought up on your phone. You torque the altitude and azimuth adjusters on the GEM until Polaris is at the exact spot in the reticle that the app indicates. You know precision in the alignment step assures no drift in the image throughout the night...and you are thankful you spent extra money on that heavy Takahashi mount that lets you NAIL your alignment.

You go into TheSkyX, make sure that it "sees" the mount, connect to it, and then you select Betelguese, surprised at how faint it looks compared to last year. Using the handpad of the mount, you "slew" the scope toward the star using your small finder-scope. You connect to your imaging camera in SharpCap, turn on your camera's cooler to -15 celsius, and you begin short, repeated focus exposures hoping that Betelguese is on the screen. Certainly it is, but you adjust focus to make it look like less of a smudge. It's also a little off-center, so you nudge the hand-box until it's right in the middle and then you "sync" on the star in TheSkyX. Now, you feel good about using the planetarium software to go anywhere you want in the night sky.

Of course you really aren't focused yet. You've finally learned your lesson after scores of wasted data due to too many assumptions about being "in focus." So tonight, as in all nights now, you begin your typical focus procedure with a mag 5 star and a Bahtinov mask. You hope to get a robotic focuser and total automation software at some point in the future, but for now you'll just adjust your focus by hand.

Then swing the mount over to another, less bright star, and you repeat the same procedure for the guide camera, bringing it to focus and then "calibrating" it on the current star, so the "guider" can do its job accurately and precisely.

It is now 30 minutes later from the moment you first saw Polaris and you figure that there's about 30 minutes of twilight remaining until you can actually start an image. You are definitely getting good at this! So, you use the time to take some dark frames with the camera. Easy enough. Ten 3 minutes darks in a row...glad the software does it all for me with the push of a button.

So you celebrate being "ready" by taking seat and sipping on the beer you opened an hour ago. Thankfully, it's a chilly night so the beer only warmed up enough that you can really taste the malt...just as you like it!

You decide on a target for the night...the Rosette Nebula...and you know that you have the right equipment for the job. When dark enough, you select NGC 2244 (which is the star cluster within the core) within TheSkyX and you press "slew." Sounding like a jet engine, the mount does a meridian flip from east to west, bring the nebula closer and closer on target until, after a minute, you are sure the mount did its job. But to be certain, you do a 10 second image with the main camera to see if you recognize the field...and truly the cluster is right in the center of the laptop screen. Yay!

Next, you bring up your guide camera, take a 1 second exposure, and see if there is a bright enough star to "guide" on. Yep, lots of bright stars here. So you choose one that isn't over-saturated and you tell the software to begin auto-guiding. You know that now if the star moves in any of those 1 second images, the software will bump the mount automatically to keep the star in the center. At this moment, you are thankful you spent all that extra money to get away from your old CG-5 mount, which only seemed to calibrate and guide accurately half of the time.

Finally, you are able to setup a sequence of exposures to be taken with the imaging camera. Your camera is one-shot color (OSC), so you are glad its just a matter of taking a whole bunch of those pictures instead of needing to capture through RGB filters with a grayscale camera. But isn't digital wonderful! You can't wait to "stack" all 100 three minute images you take over the course of the night. Of course, the temperature is dropping quite a bit, so you know you'll have to REFOCUS your f/5 refractor after about 40 minutes because of focal shift. You are determined to do so, since you are tired of being lazy and seeing your images become more and more out of focus as your evenings goes by. Truly, focusing is job ONE in this hobby!

Your first image of the Rosette appears about 3 minutes later. It's all dark on the screen, but you know that the monitor can't show your 12-bit image on screen since the software's "screen stretch" setting expects 16-bits. So, you manually move the slider to reveal all the thick ionized hydrogen and dust, along with some quite bright and round stars.

Nothing to change now...there's one beer to be consumed between each focus run. Might as well sit back with some binoculars are enjoy the night.

The ideal evening as an astro-imager has taken place. You pack up in the morning after taking some "flats" with your EL panel, happy with the knowledge that you have so many fine sub-exposures of a great deep sky object.

The night of an astroimager starts with hopeful enthusiasm. Last night, after all, was a washout. Tonight is a little windy, but that's not an ender, like so much of the weather. Hopefully, the wind doesn't pick up any more, since last month you had much of your "data" ruined by the wind-induced vibrations to your mount. That's why, tonight, you've chosen to shoot with your smaller refractor. Shorter focal lengths means more room for error...so let the wind blow a little.

Setup begins after dinner - a window of 90 minutes of remaining daylight to make sure everything is ready by dusk. First thing you do is put up your small table and the second thing you do is pop open a beer to place on the table...because that's important..

Then, you pull out your big tripod for the "mount," sticking one of the three legs in the general direction of "north." Close enough is all that matters for now, since you'll need to see Polaris before you can actually "polar align" the mount.

Next is your equatorial mount "head". Heavy, weighing about 40 lbs. itself, you are thankful that you ditched the $400 case you normally keep it in...it's such a pain trying to grab it out of the foam padded case! From the back of the SUV to the tripod, you strain to lift up the GEM (German Equatorial Mount), spinning it around toward the northern-placed leg prior to attaching the bolts to connect the two.

Counterweights are next. You brought only one to this dark sky site since your small refractor only needs one. It slides on and you bind it to the counterweight shaft with no real care about where - you'll balance the mount later. Oh, but don't forget the stop that screws into the end of the counterweight shaft. You remember very well the time you forgot the stop and a 12 lbs. counterweight slammed into your foot!

You slide the Losmandy rail containing the telescope's rings into the mount's saddle and lock it down. You open the rings, insert the telescope, and lock down the rings. Again, not caring about actual position.

Then it's the finderscope, guidescope, camera adapters, and two separate cameras - your imaging camera which connects to your small refractor and a "guide" camera that goes with the guidescope.

Cables are next, which means out come the laptop PC. USB cables, one each for the mount, imaging camera, and guide camera are run to a USB hub stuck with double-sided tape to that Losmandy rail. Then, a long USB cable goes from hub to laptop. You also run a separate serial cable from your guide-camera to the mount. Power for the mount and both cameras goes to a DIY terminal strip also mounted at the rail, and a power cable connects the strip to a large DC 12v battery. The battery will power all your gear for the duration of the night. You are ingenious!

You tidy up the cables a little bit with zip-ties to keep them from hanging on stuff. And then you release the mounts RA lock to begin balancing the mount. Holding the counterweight shaft to keep it the scope from flying towards the ground, you loosen the counterweight and slide it lower, intermittently locking it in place to see if it perfectly balances out the small, but surprisingly heavy refractor, locking the mount when you achieve balance. You then repeat in the DEC axis, sliding the Losmandy rail in the saddle until you are convinced it will not spin out of control if you let go.

You power up all the hardware, including the laptop, equipped with Windows 7 (because 10 might not work yet with your drivers and you hated 8). When convinced that everything is working, you start-up your chosen planetarium software, TheSkyX, and you wait for the excitement to begin.

"Polar alignment" begins the moment you can see Polaris, since now you can use your polar alignment scope. Turns out you were remarkably close to it when you first plopped down the mount...you are getting good at this stuff! With allen wrench in hand, you flip on the illuminated polar reticle and compare it to the one shown on an app you've brought up on your phone. You torque the altitude and azimuth adjusters on the GEM until Polaris is at the exact spot in the reticle that the app indicates. You know precision in the alignment step assures no drift in the image throughout the night...and you are thankful you spent extra money on that heavy Takahashi mount that lets you NAIL your alignment.

You go into TheSkyX, make sure that it "sees" the mount, connect to it, and then you select Betelguese, surprised at how faint it looks compared to last year. Using the handpad of the mount, you "slew" the scope toward the star using your small finder-scope. You connect to your imaging camera in SharpCap, turn on your camera's cooler to -15 celsius, and you begin short, repeated focus exposures hoping that Betelguese is on the screen. Certainly it is, but you adjust focus to make it look like less of a smudge. It's also a little off-center, so you nudge the hand-box until it's right in the middle and then you "sync" on the star in TheSkyX. Now, you feel good about using the planetarium software to go anywhere you want in the night sky.

Of course you really aren't focused yet. You've finally learned your lesson after scores of wasted data due to too many assumptions about being "in focus." So tonight, as in all nights now, you begin your typical focus procedure with a mag 5 star and a Bahtinov mask. You hope to get a robotic focuser and total automation software at some point in the future, but for now you'll just adjust your focus by hand.

Then swing the mount over to another, less bright star, and you repeat the same procedure for the guide camera, bringing it to focus and then "calibrating" it on the current star, so the "guider" can do its job accurately and precisely.

It is now 30 minutes later from the moment you first saw Polaris and you figure that there's about 30 minutes of twilight remaining until you can actually start an image. You are definitely getting good at this! So, you use the time to take some dark frames with the camera. Easy enough. Ten 3 minutes darks in a row...glad the software does it all for me with the push of a button.

So you celebrate being "ready" by taking seat and sipping on the beer you opened an hour ago. Thankfully, it's a chilly night so the beer only warmed up enough that you can really taste the malt...just as you like it!

You decide on a target for the night...the Rosette Nebula...and you know that you have the right equipment for the job. When dark enough, you select NGC 2244 (which is the star cluster within the core) within TheSkyX and you press "slew." Sounding like a jet engine, the mount does a meridian flip from east to west, bring the nebula closer and closer on target until, after a minute, you are sure the mount did its job. But to be certain, you do a 10 second image with the main camera to see if you recognize the field...and truly the cluster is right in the center of the laptop screen. Yay!

Next, you bring up your guide camera, take a 1 second exposure, and see if there is a bright enough star to "guide" on. Yep, lots of bright stars here. So you choose one that isn't over-saturated and you tell the software to begin auto-guiding. You know that now if the star moves in any of those 1 second images, the software will bump the mount automatically to keep the star in the center. At this moment, you are thankful you spent all that extra money to get away from your old CG-5 mount, which only seemed to calibrate and guide accurately half of the time.

Finally, you are able to setup a sequence of exposures to be taken with the imaging camera. Your camera is one-shot color (OSC), so you are glad its just a matter of taking a whole bunch of those pictures instead of needing to capture through RGB filters with a grayscale camera. But isn't digital wonderful! You can't wait to "stack" all 100 three minute images you take over the course of the night. Of course, the temperature is dropping quite a bit, so you know you'll have to REFOCUS your f/5 refractor after about 40 minutes because of focal shift. You are determined to do so, since you are tired of being lazy and seeing your images become more and more out of focus as your evenings goes by. Truly, focusing is job ONE in this hobby!

Your first image of the Rosette appears about 3 minutes later. It's all dark on the screen, but you know that the monitor can't show your 12-bit image on screen since the software's "screen stretch" setting expects 16-bits. So, you manually move the slider to reveal all the thick ionized hydrogen and dust, along with some quite bright and round stars.

Nothing to change now...there's one beer to be consumed between each focus run. Might as well sit back with some binoculars are enjoy the night.

The ideal evening as an astro-imager has taken place. You pack up in the morning after taking some "flats" with your EL panel, happy with the knowledge that you have so many fine sub-exposures of a great deep sky object.

After 23 years in this hobby, I'm still waiting for a night like that. Not that I haven't been close. I'm good enough now, my equipment reliable enough now, that I do pretty well on most nights. But there's always something you didn't expect. The astronomy gods always have a surprise, either weather or something mechanical or a stupid Windows update that you forgot to disable!

There isn't a huge challenge involved with an image like this. Taken in 2015, Devil's Tower in Wyoming is awesome, especially when you can catch the Big Dipper with it. Despite a full moon, knowing how to properly expose the image takes some practice. But practice aside, this type of image is a great way to start in this hobby. Taken with Nikon D810a DSLR on tripod.

There isn't a huge challenge involved with an image like this. Taken in 2015, Devil's Tower in Wyoming is awesome, especially when you can catch the Big Dipper with it. Despite a full moon, knowing how to properly expose the image takes some practice. But practice aside, this type of image is a great way to start in this hobby. Taken with Nikon D810a DSLR on tripod.

FIGURING IT ALL OUT

For today's beginner to the hobby, it seems less obvious that the learning curve with digital is far beyond that which us old timers experienced with film. Those were the easy days. In fact for us, the earlier adopters to digital CCDs, we had a need to evolve and LEARN a whole new, complicated way of imaging the night sky. More electronics, more cables, more things that could go wrong.

Learning this new frontier of imaging wasn't easy. It wasn't like we had a ton of resources. Yes, we had an early Internet, but there was nothing on the internet in which to learn digital astro-imaging other than some astronomy forums or "use-nets" where many of us would post our experiences, pitch ideas, and show the fruits of our efforts with some rather ugly (by today's standards) astrophotos. So, we had to experience a lot of failure, define some new experiences, and read a few textbooks before we started to see some good progress.

Most importantly, unlike today, we didn't have people to teach or mentor us. Those people didn't exist. There were experts within different areas of what we needed to know, which were definitely an important part of our learning. There were trailblazers who accomplished a variety of firsts in our hobby, leaving some coat-tails onto which the rest of us rode. But for the most part, from the time we started until the time many of us felt we "mastered" any aspects of it that we cared about (there's so many ways that this hobby can express itself), it took many, many years.

Today, of course, is different. The problem is not a lack of learning resources, but rather there are so many resources that you will likely not know where to start. In fact, I would suggest that you need a filter (just like our cameras); you will need a way to sort out all the information (and misinformation) to find out what is worth your time. Certainly, you need to be careful, as there are opinions out there that can confuse you or mislead you as much as help you.

And in fact, if you are reading this, you are undoubtedly going through the process of learning this difficult hobby. But, perhaps unlike anything else you have read, I will attempt to show you how to put together a program of study from the enormous amount of largely disconnected resources out there. And then we will put together a method of practicing astrophotography. And if you don't really need such a program, you should still get plenty of mileage out of some of the many tips and tricks.

For today's beginner to the hobby, it seems less obvious that the learning curve with digital is far beyond that which us old timers experienced with film. Those were the easy days. In fact for us, the earlier adopters to digital CCDs, we had a need to evolve and LEARN a whole new, complicated way of imaging the night sky. More electronics, more cables, more things that could go wrong.

Learning this new frontier of imaging wasn't easy. It wasn't like we had a ton of resources. Yes, we had an early Internet, but there was nothing on the internet in which to learn digital astro-imaging other than some astronomy forums or "use-nets" where many of us would post our experiences, pitch ideas, and show the fruits of our efforts with some rather ugly (by today's standards) astrophotos. So, we had to experience a lot of failure, define some new experiences, and read a few textbooks before we started to see some good progress.

Most importantly, unlike today, we didn't have people to teach or mentor us. Those people didn't exist. There were experts within different areas of what we needed to know, which were definitely an important part of our learning. There were trailblazers who accomplished a variety of firsts in our hobby, leaving some coat-tails onto which the rest of us rode. But for the most part, from the time we started until the time many of us felt we "mastered" any aspects of it that we cared about (there's so many ways that this hobby can express itself), it took many, many years.

Today, of course, is different. The problem is not a lack of learning resources, but rather there are so many resources that you will likely not know where to start. In fact, I would suggest that you need a filter (just like our cameras); you will need a way to sort out all the information (and misinformation) to find out what is worth your time. Certainly, you need to be careful, as there are opinions out there that can confuse you or mislead you as much as help you.

And in fact, if you are reading this, you are undoubtedly going through the process of learning this difficult hobby. But, perhaps unlike anything else you have read, I will attempt to show you how to put together a program of study from the enormous amount of largely disconnected resources out there. And then we will put together a method of practicing astrophotography. And if you don't really need such a program, you should still get plenty of mileage out of some of the many tips and tricks.

|

DEVELOPING AN APPROACH

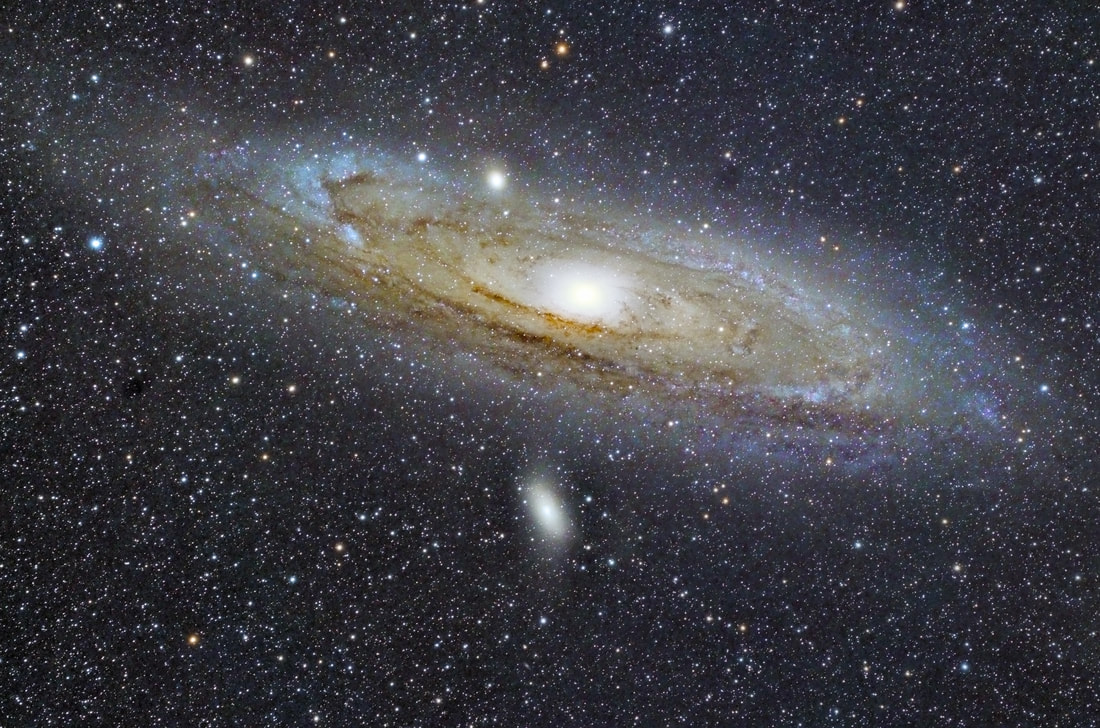

If you are anything like me, you dreaded taking classes in high school and college for the subjects you hated. For me, I despised literature. The act of reading entire books or short stories to learn a small snippet about something I didn't care about seemed a waste of my time. Pass me the "Cliffs Notes" or just show me the movie! But what sets hobbies apart from high school is that we genuinely want to do it and we are typically willing to read the entire book. We often have sufficient motivation, but this alone does not assure that we are willing to do what it takes to properly learn it. This hobby is a challenge...but I knew that going in...and it was honestly my driving force for learning it. I embraced every failure I had because I knew that I was getting better regardless of the result. And I failed hard. Truth be known, my first efforts were hooking my Nikon F2 to my Meade LX200 at prime focus. It didn't take me long to realize that I REALLY needed to work up to that type of photography. Do you know how depressing it is to have your first 6 rolls of film developed and get nothing but trash for your efforts? I say this because I find that most people are more interested in the end result rather than the "journey." They see images like those in FIGURE 1 below and they don't realize how difficult it really is. They buy a bunch of expensive equipment, assuming they'll have what it takes to use it, but it becomes a classic case of biting off more than they can chew.

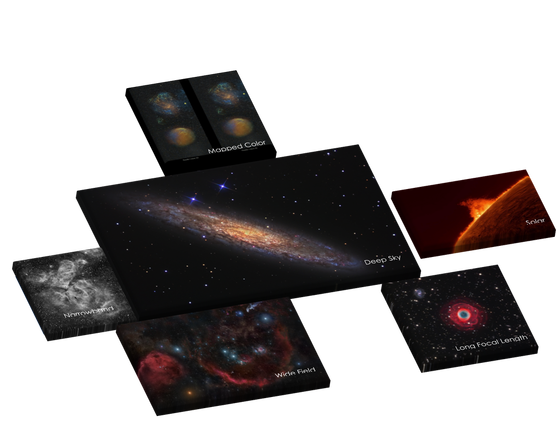

FIGURE 1 - The form of the Astrophotography you wish to learn can play a large role in the ease in which the learning occurs. While much of your choice in this area is dictated by equipment availability, budget, and location, the willing learner needs to understand the demands and complexities of each imaging form and how much time and effort you are willing to devote to having success. This goes beyond the scope of this article, but be sure to spend some time researching why some images are just a heckuva lot easier to take (and process) than others.

A SENSIBLE PROGRESSION Rethinking my approach, I decided to begin with the more fundamental of techniques, which was film exposures using a tripod and wide angle camera lenses. Star trails, Milky Way vistas, nightscapes, lightning pictures, and constellation images were my objectives. I followed that with "piggyback" photography, achieving my most exciting successes. This is when I truly fell in love with astrophotography. And only then did I really feel prepared to work my way up the ladder to the real hard stuff. For today's beginner serious about photography, you probably already have a DSLR and a tripod, so it just makes sense to begin with images like the Devli's Tower shot shown earlier. Doing so, I think newbies will better understand the level of commitment required without being thrown into "prime focus," long exposure imaging through a telescope. You will also have a better idea of what your next purchases should be.

From there, I would suggest a similar progression (seen in FIGURE 2 below), regardless of how you approach your learning in the sections that follow. It's not all THAT challenging doing nightscapes with a DSLR on a tripod and those early successes will drive you forward, very analogous to the way I did it with film. That same equipment can then be used to mount onto the top of your first equatorially-mounted scope, using your own camera lenses while the scope serves as the tracking platform. This is what I mean by "piggybacking." I consider it a powerful gateway to all other forms long exposure, deep sky object (DSO) imaging using telescopes. Unfortunately, "piggybacking" seems to be the imaging method talked about the LEAST (see Sidebar: Piggybacking Power! for more details).

FIGURE 2 - Jumping into the hobby at the extreme end can prove to be difficult for ANY learner. By starting at left in this diagram and then working toward the right, it assures that your learning becomes gradual and consistent, all the while producing some nice images as you go. Shown left to right are a DSLR & tripod for wide-fields, a tripod "tracker" setup, a piggyback rig, a short focal length deep-sky setup, and a long focal length deep-sky setup.

|

Sidebar: Piggybacking Power!One of the things that becomes quickly evident while practicing this hobby is that the challenge to get good images rises exponentially with the focal length of your setup. As shown in FIGURE 2 where there is a progression of optical focal lengths from left to right, the use of short-focal length camera lenses makes a ton of sense. It's just plain easier!

Tripod shots will typically be less than 30 seconds or so, which is the maximum set exposure time of most DSLR cameras without either using a shutter-release in "B" (bulb) mode or using an intervalometer (hardware or software) to automate your exposures. The "rule of 500" gives you a great rule of thumb for estimating the maximum exposure possible for stars before they start to trail, which is basically dividing 500 by the focal length of your lens. It will vary according to where in the sky you are shooting and the "crop-factor" of your camera sensor, but the article linked above will give you a handy chart so you don't have to compute those figures each time. After shooting stationary tripod images of star-trails, constellation, and the Milky Way anywhere from 14mm to 50mm - or perhaps even doing some other creative night photography (see images above) - the next step will definitely become "tracked" shots that move with the stars. This allows you to do much longer camera exposures - you bought that intervalometer, right? That might necessitate the purchase of a dedicated-tracker (either commercial or home-made). But most people just set the camera on a motorized equatorial-mount. Doing so could occur in three forms: 1.) Mounting the camera with lens directly on a German-Equatorial mount (GEM), 2.) Mounting it atop a Schmidt-Cassegrain (or any fork mounted scope) with an equatorial "wedge," or 3.) piggybacking it atop (or alongside) your main telescope on a GEM. Shown above - Various ways to piggyback a camera. Piggyback DSLR with large lens atop a fork & wedge mounted SCT (upper left), a DSLR fixed atop a refractor with GEM (lower left), and a variety of cameras mounted in both piggyback and side-by-side configurations (right).Whichever way it's done, piggybacking a scope is simple and the quality of the tracking EQ mount doesn't have to be extreme. Most people with DSLRs likely have 200mm or 300mm lenses in their camera bags, and I cannot think of a single electronic tracking equatorial mount that cannot be made to give stable, long exposures (within reason) of wide-field deep sky objects. It further introduces you to the skills of polar-aligning a telescope, calibrating images, and refining focus. It can also accommodate multiple camera setups for simultaneous image capture. The feasibility of this type of approach, from the standpoint of limitations, ends somewhere around the 300mm focal length mark. Nicer GEM mounts and the more sturdy fork-mounted SCTs can provide sufficient platforms to take exceedingly long exposures; however, large lenses can cause some setups to oscillate with vibrations, become affected by wind, or require a "guiding" camera to keep tracking centered. Even so, before you purchase those fancy new telescope optics, spending extra on the mount FIRST makes total sense when you consider that you may have enough camera lenses to last you quite a while! In fact, this should prompt the question as to why we think we need a fast 3" apochromatic imaging scopes to use with a DSLR? For example, while a Skywatcher Esprit 80mm f/5 telescope is pretty slick for 400mm focal length images, you might not be gaining much over the Canon 300mm f/4 "L" series lens you already have in your camera bag. Add a 1.4x telecompressor for 420mm f/5.6 images, and you begin to see the virtue of saving that money for either more telescope mount or a medium focal length telescope in the 500mm or greater range. Of course, if you are using a dedicated astro CCD camera, you'll be very inclined to buy such telescopes, though be aware that some such cameras even have ways to adapting it to your DSLR camera lenses. The longer you stick with your arsenal of camera lenses, the more versatility you will have. And though you are progressing up the learning curve by increasing focal lengths, it's not like a your camera lenses ever become obsolete. We always have the need to shoot such images...and the best way to take advantage of all those toys in your camera bag is to come up with a piggyback rig! |

My hope and my assumption, if you are reading this, is that you've already figured out how challenging everything is, yet you are determined to dive into your education, undaunted by the journey before you.

So here, having fully committed to your equipment investment and the price of the learning to come, let's look at three general approaches to learning today's astrophotography. There's the "tutorial approach," where we look for step-by-step processes or individual activities to initiate us to our learning. We have a "theory approach," in which we consider the overall concepts and overarching themes of what we are doing. And there's the "guided approach," where we enlist a teacher, mentor, or community to help us with our learning.

SPOILER ALERT: All three approaches are necessary if you hope to learn in the most efficient of ways, regardless of where you are in your progression. For more about the overall process of learning just about anything, check out the Sidebar: How to Learn Anything.

So here, having fully committed to your equipment investment and the price of the learning to come, let's look at three general approaches to learning today's astrophotography. There's the "tutorial approach," where we look for step-by-step processes or individual activities to initiate us to our learning. We have a "theory approach," in which we consider the overall concepts and overarching themes of what we are doing. And there's the "guided approach," where we enlist a teacher, mentor, or community to help us with our learning.

SPOILER ALERT: All three approaches are necessary if you hope to learn in the most efficient of ways, regardless of where you are in your progression. For more about the overall process of learning just about anything, check out the Sidebar: How to Learn Anything.

Wanna build a Starship Enterprise and don't know how to start? We'll click on this picture for a tutorial on how to make one!

Wanna build a Starship Enterprise and don't know how to start? We'll click on this picture for a tutorial on how to make one!

THE TUTORIAL APPROACH

If I want to build a model of something, let's say, the Starship Enterprise, then I wouldn't have a clue on how start it. And for a scratch build, I wouldn't even know the right materials, even though I've seen people use balsa wood for stuff. Nor would I know the appropriate tools, except for being able to use a digital multimeter to help wire an LED circuit.

Wouldn't it just be nice if somebody posted an "Instructables" tutorial online detailing every step involved? Oh, wait...it's a little basic, but check out the one at right.

You can search the Internet for building or fixing ANYTHING now-a-days and you'll undoubtedly find a "tutorial" on some aspect of it. Keeping with the sci-fi theme, do you want to build a Millennium Falcon out of Legos? Well I can point you toward a PDF file showing THOUSANDS of steps toward completing this wonderful achievement!

Building a ship that can make the Kessel run in 12 parsecs is very similar to astrophotography...and a bunch of tutorials can be an extremely valuable way to get started on a hobby when you have no other idea of how to proceed...

For many, especially those driven to take "nightscapes" or time-lapses with a DSLR, then jumping from tutorial-to-tutorial might be all that's needed. ISO 1600...check. Good focus...check. Compute exposure length...ready to go! (see Sidebar: Piggybacking Power! for the "Rule of 500")

Tutorials, or even simple lists, reminding us of how to do some of the more difficult tasks in the hobby are all over the Internet. Or, thankfully, many wonderful people have published their entire "workflow," or their the step-by-step process in which we can emulate.

Step-by-step, inch-by-inch, you can accomplish the task. Rinse. Lather. Repeat.

It's been said that to master anything, we need to do it for 10,000 hours. Practice, practice, practice! And just about any tutorial can provide you with some kind of meaningful practice. We don't even need to understand what we are doing in many cases...the recipe for success is on the Internet.

Hopefully you will strive to supplement your learning with some extra reading, but the Tutorial Approach does promote a good pathway to success, especially for those who don't have a clue how to start.

If I want to build a model of something, let's say, the Starship Enterprise, then I wouldn't have a clue on how start it. And for a scratch build, I wouldn't even know the right materials, even though I've seen people use balsa wood for stuff. Nor would I know the appropriate tools, except for being able to use a digital multimeter to help wire an LED circuit.

Wouldn't it just be nice if somebody posted an "Instructables" tutorial online detailing every step involved? Oh, wait...it's a little basic, but check out the one at right.

You can search the Internet for building or fixing ANYTHING now-a-days and you'll undoubtedly find a "tutorial" on some aspect of it. Keeping with the sci-fi theme, do you want to build a Millennium Falcon out of Legos? Well I can point you toward a PDF file showing THOUSANDS of steps toward completing this wonderful achievement!

Building a ship that can make the Kessel run in 12 parsecs is very similar to astrophotography...and a bunch of tutorials can be an extremely valuable way to get started on a hobby when you have no other idea of how to proceed...

- With any mount, there's probably a tutorial online on how to set it up.

- Setting your DSLR for optimum exposures can be discovered with a simple Google search.

- If you want to learn how to sharpen your image, then I'm sure you'll see a thousand videos on YouTube detailing the process.

- For those who want to hit the ground running, one of the zillion "How to Shoot the Milky Way" articles might prove to be a great resource for you.

For many, especially those driven to take "nightscapes" or time-lapses with a DSLR, then jumping from tutorial-to-tutorial might be all that's needed. ISO 1600...check. Good focus...check. Compute exposure length...ready to go! (see Sidebar: Piggybacking Power! for the "Rule of 500")

Tutorials, or even simple lists, reminding us of how to do some of the more difficult tasks in the hobby are all over the Internet. Or, thankfully, many wonderful people have published their entire "workflow," or their the step-by-step process in which we can emulate.

Step-by-step, inch-by-inch, you can accomplish the task. Rinse. Lather. Repeat.

It's been said that to master anything, we need to do it for 10,000 hours. Practice, practice, practice! And just about any tutorial can provide you with some kind of meaningful practice. We don't even need to understand what we are doing in many cases...the recipe for success is on the Internet.

Hopefully you will strive to supplement your learning with some extra reading, but the Tutorial Approach does promote a good pathway to success, especially for those who don't have a clue how to start.

THE THEORY APPROACH

What if you wanted to be a good basketball coach? Would you win a lot of games if you ran the same plays as your own high school coach or if you watched a few videos on how to coach? Well, perhaps for a while. But what if your players change or the rules change or the competition and style of play changes? Will you be able to adjust?

What if you wanted to be a good basketball coach? Would you win a lot of games if you ran the same plays as your own high school coach or if you watched a few videos on how to coach? Well, perhaps for a while. But what if your players change or the rules change or the competition and style of play changes? Will you be able to adjust?

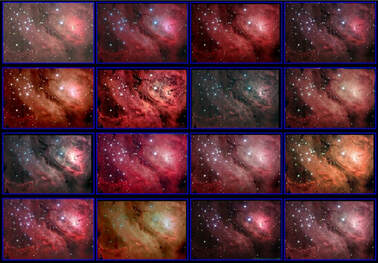

FIGURE 3 - Gaining valuable information about an image despite optimal results has great merits. This two-frame mosaic portion of the Rosette Nebula is a study in the importance of SNR vs. "seeing" conditions. The noisy right hand side of the image taken during worse seeing had easily 50% more imaging time compared to the left side of the image. Each frame, taken on subsequent nights, demonstrated one of the most important discoveries of my own learning - that the quality of my acquisition is just as important as the amount of time I spend DOING my acquisition.

FIGURE 3 - Gaining valuable information about an image despite optimal results has great merits. This two-frame mosaic portion of the Rosette Nebula is a study in the importance of SNR vs. "seeing" conditions. The noisy right hand side of the image taken during worse seeing had easily 50% more imaging time compared to the left side of the image. Each frame, taken on subsequent nights, demonstrated one of the most important discoveries of my own learning - that the quality of my acquisition is just as important as the amount of time I spend DOING my acquisition.

Tutorials over astroimaging can yield success on a regular basis, but it's only by understanding a little about imaging theory that you can hope to duplicate your successes on multiple nights on a variety of images using a variety of hardware and software.

For example, I would argue that using a digital camera to get good "data" is a nice accomplishment, but understanding the nature of that data and how it can be improved the following night is quite another. Moreover, knowing how a TEC-cooled astrocamera can yield another level of significant improvement is doubly empowering!

Such is the basis of the Theory Approach to learning astro-imaging.

Your ability to respond to the ever-changing nature of events and the wide range of complexity depends on your ability to understand the whys and hows of the hobby. In other words, do you know enough about the overall nature of what you are doing to be consistently successful?

Please forgive the minor digression, but as a high school teacher, my career began by teaching Career and Technology courses, chiefly on how to use software on a PC to do word processing, spreadsheets, and databases. Back in 1995, there were a variety of software packages that could be learned, and no single software publisher had the kind of market-share that Microsoft enjoys today with their MS Office products. So, it became important for us to teach the overall concepts of those applications, even though we practiced using a single software package. Yes, we used an early version of MS Office, but it could have very well been ClarisWorks, which I favored personally on Macintosh at the time.

In astronomy, there IS NO STANDARD HARDWARE OR SOFTWARE PLATFORM. Your results will be different from my results, even if we use a lot of the same gear. To be able to understand these differences, there's a huge benefit to reading some good articles on webpages, magazines and books covering topics like SNR, sampling, binning, histograms, deconvolution/convolution. Likewise, knowing something about astronomy gear can help you know the limits you might expect with your own gear and whether or not a change or upgrade might be in order?

While you might not understand "theory" the first time you read the theory-heavy articles at an excellent webpage like All About Astro, you certainly might after a year passes, after you've seen enough of the concepts in your practice. It's a systematic approach whereby we categorize our experiences, realizing how all the pieces fit together, and how new experiences fit into the overall picture.

It's in knowing that this week's image of the Rosette Nebula might not produce a pleasing end product, but there might be something far more valuable in having made the attempt (see FIGURE 3 above). This is what makes you better at this stuff. It turn's failures into learning experiences...which equates to less failure in the future.

For example, I would argue that using a digital camera to get good "data" is a nice accomplishment, but understanding the nature of that data and how it can be improved the following night is quite another. Moreover, knowing how a TEC-cooled astrocamera can yield another level of significant improvement is doubly empowering!

Such is the basis of the Theory Approach to learning astro-imaging.

Your ability to respond to the ever-changing nature of events and the wide range of complexity depends on your ability to understand the whys and hows of the hobby. In other words, do you know enough about the overall nature of what you are doing to be consistently successful?

Please forgive the minor digression, but as a high school teacher, my career began by teaching Career and Technology courses, chiefly on how to use software on a PC to do word processing, spreadsheets, and databases. Back in 1995, there were a variety of software packages that could be learned, and no single software publisher had the kind of market-share that Microsoft enjoys today with their MS Office products. So, it became important for us to teach the overall concepts of those applications, even though we practiced using a single software package. Yes, we used an early version of MS Office, but it could have very well been ClarisWorks, which I favored personally on Macintosh at the time.

In astronomy, there IS NO STANDARD HARDWARE OR SOFTWARE PLATFORM. Your results will be different from my results, even if we use a lot of the same gear. To be able to understand these differences, there's a huge benefit to reading some good articles on webpages, magazines and books covering topics like SNR, sampling, binning, histograms, deconvolution/convolution. Likewise, knowing something about astronomy gear can help you know the limits you might expect with your own gear and whether or not a change or upgrade might be in order?

While you might not understand "theory" the first time you read the theory-heavy articles at an excellent webpage like All About Astro, you certainly might after a year passes, after you've seen enough of the concepts in your practice. It's a systematic approach whereby we categorize our experiences, realizing how all the pieces fit together, and how new experiences fit into the overall picture.

It's in knowing that this week's image of the Rosette Nebula might not produce a pleasing end product, but there might be something far more valuable in having made the attempt (see FIGURE 3 above). This is what makes you better at this stuff. It turn's failures into learning experiences...which equates to less failure in the future.

THE GUIDED APPROACH

Teaching is one of the more undervalued or under-appreciated professions around (in my biased opinion). Teachers are necessary in the development of the learner. If a student didn't have anybody to guide instruction, answer their questions, give customized practice, grade the quality of their work, and assess mastery of their learning objectives, then there would no longer be the need for schools, colleges, and universities.

When you attempt to learn ANYTHING without a teacher or mentor, no matter who you are, you are doing so at a handicap. Those that recognize this fact will favor a Guided Approach to the hobby.

Teaching is one of the more undervalued or under-appreciated professions around (in my biased opinion). Teachers are necessary in the development of the learner. If a student didn't have anybody to guide instruction, answer their questions, give customized practice, grade the quality of their work, and assess mastery of their learning objectives, then there would no longer be the need for schools, colleges, and universities.

When you attempt to learn ANYTHING without a teacher or mentor, no matter who you are, you are doing so at a handicap. Those that recognize this fact will favor a Guided Approach to the hobby.

RESOURCES

A good mentor could lead you to good resources, but if you are reading this article, then it's likely you want the challenge of learning a few things all by yourself. I am often asked what resources I believe have some educational value to them, so now let's discuss some of the more valuable resources available to you in your journey to be a good astro-imager.

Articles, Videos, and Podcasts

Using the Internet to read articles on various topics or to watch videos about similar experiences is a great way to get going. In fact, I have saved myself thousands of dollars by watching YouTube videos alone - fixing my own appliances and "DIY-ing" most of the things around my home. But while I can typically fix my own HVAC system, it doesn't make me an expert on it. Even so, people are normally impressed by my abilities as "Mr. Fix-it." In the same way, you should know that people WILL be impressed by your astrophotography, even if the only thing you ever do is learn via YouTube videos and Internet articles. The resources are THAT plentiful, unlike back when I first learned the hobby.

A good mentor could lead you to good resources, but if you are reading this article, then it's likely you want the challenge of learning a few things all by yourself. I am often asked what resources I believe have some educational value to them, so now let's discuss some of the more valuable resources available to you in your journey to be a good astro-imager.

Articles, Videos, and Podcasts

Using the Internet to read articles on various topics or to watch videos about similar experiences is a great way to get going. In fact, I have saved myself thousands of dollars by watching YouTube videos alone - fixing my own appliances and "DIY-ing" most of the things around my home. But while I can typically fix my own HVAC system, it doesn't make me an expert on it. Even so, people are normally impressed by my abilities as "Mr. Fix-it." In the same way, you should know that people WILL be impressed by your astrophotography, even if the only thing you ever do is learn via YouTube videos and Internet articles. The resources are THAT plentiful, unlike back when I first learned the hobby.

|

Many of these resources will fully support your desire for either a Tutorial or Theory Approach to the hobby. At All About Astro, I tend to speak more about the theory of what we do, since I have experience over a wide range of equipment, software, and imaging types. I also recognize that step-by-step tutorials are already plentiful on the Internet.

Two of the best websites to peruse are those by Jerry Lodriguss and Starizona. Both sites have highly recommended "how-to" tutorials and articles about imaging theory. Jerry has also published several topical series of tutorials which can be purchased online both on his website and at various vendors. For the most amazing information about DSLRs and other technical aspects of the hobby, Roger Clark's website is an absolute treasure trove of objectively tested information. As for image processing, I have to recommend Harry's Astroshed for some of the best free video tutorials around. It's where your PixInsight education should begin, among other things. YouTube is a terrific resource when you want astronomy-related information and it should be your primary way of understanding more about the objects you are shooting. I particularly like many of Brady Haran's "channels," specifically Sixty Symbols, DeepSkyVideos, and Numberphile. Like Numberphile, 3Blue1Brown is also wonderful if you are a math geek. Make sure you subscribe to such channels so you won't miss any of his very regularly published videos. YouTube also has some interesting videos by some aspiring imagers. Among my favorite imaging channels are AstroBackyard, AstroBiscuit, Dylan O'Donnell, and Chuck's Astrophotography. There's also a plethora of one-off videos for taking nightscapes and Milky Way time-lapses that have received thousands upon thousands of views. So yeah, fire up YouTube and see if there's something that interests you. As long as you realize that most "YouTubers" (especially the imagers) aren't necessarily experts and even authoritative within the hobby (or anything else for that matter), then you can gain some valuable information in this way. Finally, there are a couple of regular astronomy and astrophotography podcasts out there. Podcasts specific to imaging are not typically long-lasting. However, you will discover via google search many single or guest episode podcasts that have been archived featuring some really nice content from some solid astrophotographers. They should not be ignored. Books and Magazines

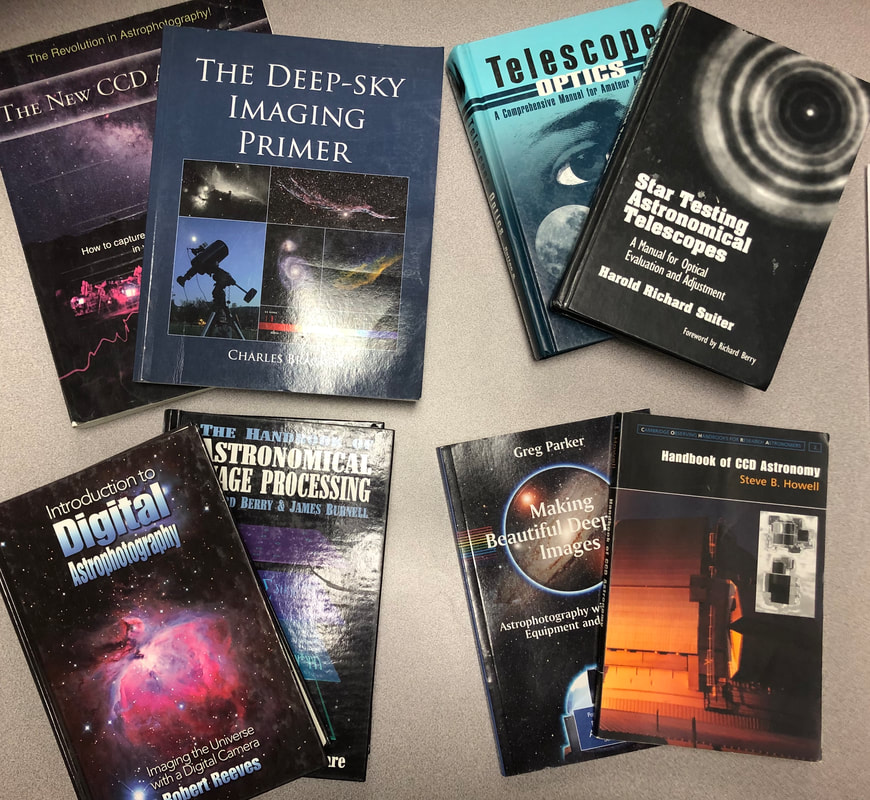

There's nothing like reading a good book. The tactile feel of paper pages cannot be replaced by digital...and there are several references out there worth your time. But if there were one book that was instrumental in helping me build a foundation on astrophotography, it was The New CCD Astronomy by Ron Wodaski. It was as close to a full, comprehensive look at the hobby that's ever existed. It's a mixture of practical and theoretical advice and topics that still holds up after all these years since it was first published. One author, Robert Reeves, has produced a variety of books through Wilmann-Bell, covering a number of topics in astrophotography. Pictured at left in FIGURE 4 is my favorite, Introduction to Digital Astrophotography, albeit I'm a little biased (see pages 3 to 5 for my contribution to it). His other texts about lunar and planetary imaging are an absolute must read for those interested in video imaging. Robert is the foremost expert on our moon among amateurs, and as of December 2023 he has a new book available, Exploring the Moon, which is an absolute must-own. Canadian authors Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer have some excellent texts as well, my all-time favorite being The Backyard Astronomers Guide (check out pp. 302-303 in the 3rd Edition for my contribution). Dickinson also delivered to us Nightwatch, which is considered a classic. Dickinson recently passed away, but Dyer still cranks out many books, magazine articles, and web-tutorials that are wonderful resources. He, like Robert, are great guys and helpful to hobbyists, even face-to-face. You'll likely run into them at any Imaging Conference or major star-party.

FIGURE 4 - Some of my favorite books, even ones not specifically about imaging, have significant value to the overall process to what we do as imagers. Pictured here are eight such books, also written about in the text of the article. It's not a conclusive list, as I have other favorites not pictured. But any text that makes you a better astronomer will also make you a better imager.

|

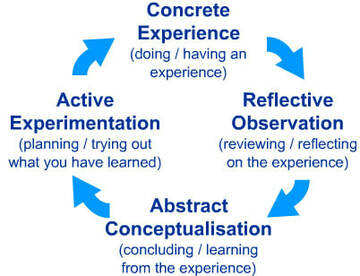

Sidebar: How to Learn AnythingWe often begin our learning with a question, which brings about some way to test and confirm the answer. But like the classic question of the chicken and the egg, what comes first, the question has to come from somewhere too.

Usually, questions comes from a previous experience. And while it'd be nice for these experiences to come from somebody else, especially for the tough learning experiences through which life puts us, it's really not the way it works. Most of us don't trust the experiences of others, even there's something to learn from it. We are stubborn creatures, often needing to go through everything ourselves. This is why you didn't know that your father was ALWAYS right until you became a father yourself. At some point, your experiences matched those of your father's. So while reading a book or watching a video can teach you something if you trust the source and are sufficiently motivated, the ideal way to learn is to jump into your own personalized and active experiences. This prompts the right questions in the right order, applicable to where you are in your own learning journey. As such, effective learning is a process; a cycle; a feedback loop. A good educator knows this cycle. There are many statements of this, but here's one popularized by David Kolb, as shown below. It would be nice to always start the cycle with a question to be answered. But in most cases, especially with beginners, the experience MUST happen first. The more we experience, the more questions we can raise, but until this happens, learning can often become frustrating because we lack the ability to verbalize what it is that seems missing. In fact, for a learner of astrophotography, my recommendation is just do something...anything. Begin with experiences, even some that do not involve the use of a camera. Download tutorials from the Internet and put in some meaningful experience. Play with multiple types of software. Watch a lot of videos; compare and contrast diverging opinions on similar topics. Just jump into the cycle and the questions will flow. Once initiated, you will see that the learning cycle works both passively and actively. The passive aspect is that internalized learning will always occur even if it doesn't seem like the lessons are structured. This gives you the comfort of knowing that nothing will be in vain; even when you didn't have a solid plan for the learning. Likewise, you will learn to value any experience as a positive learning opportunity, even if what happens seems like a total failure. Most importantly, you can think of this cycle actively. Knowing ahead of time that your questions will be best answered through a planned process of research, experimentation, and evaluation. In other words, you can successfully plan out your learning and, in a sense, become your own teacher, guiding yourself through the process like a teacher would. Albeit, you are far more likely to ask your questions out of order this way. This is because any teacher knows the "curriculum." They understand the structure of the learning: what should be practiced first, what is most important, and what prompts the best questions. They also give you valuable feedback, beyond what you can gain on your own. In other words, while you can learn anything and everything by yourself, having a teacher allows you to learn more efficiently. Teaching (or mentoring in this hobby) is less about imparting knowledge (we do that) but more about directing students down the right path of their own discovery in a way that prioritizes the learning in more of a logical, timely and holistic way. This gives ownership over the learning in a way that isn't found when always directed by a curriculum or some ordered instruction. Make no mistake about it, of all the ways and resources to learn, many of which are presented in this article, there is NO substitute for a good teacher or mentor for guidance. A mentor will keep you going in the right direction - testing the right hypotheses, giving you a way to prioritize your learning steps, and helping to encourage you every step of the way. Plus, the feedback gained will be much more rapid and valuable. |

Perhaps the most important book for hobbyists, written by expert astroimager Warren Keller, would be Inside PixInsight by Springer Press (see right). PixInsight is the most comprehensive, powerful software package for data reduction and processing, but that power only comes after overcoming a deep learning curve. Debates about PixInsight vs. Photoshop aside, it's hard to argue the growth in numbers among PixInsight users and I HIGHLY RECOMMEND this book to provide both Tutorial-based and Theory-based instructions within its 400 plus pages.

There are many other solid books, even if they are a bit dated, that you need to find, especially for those that want to dig into the theory of digital imaging. I have used the Handbook of CCD Astronomy by Steve B. Howell for many years as support for some of my published opinions on the technical aspects of the hobby. Richard Berry's The Handbook of Astronomical Image Processing is a deep foray into the technical side as well, albeit a little dated. Many texts by Michael Covington belong on your bookshelf, if only to make you look like the cool kid, but in particular he has an excellent text called Digital SLR Astrophotography that is well worth your time.

There are two classic books on astronomy optics that should be considered. Star Testing Astronomical Telescopes by Harold Suiter and Telescope Optics by Rutten & van Venrooij will each have you understanding more about choosing proper optics, how they work with a camera, and in troubleshooting optical aberrations in your images.

My friend, Dr. Greg Parker, wrote Making Beautiful Deep-Sky Images more than a decade ago now. I have always appreciated the concise and straight-forward layout of the text. Part of the Patrick Moore Practical Astronomy Series by Springer Press, Parker's book serves as an excellent survey of the hobby from equipment purchase to the published image. A similar text, but more up-to-date, would be The Deep-Sky Imaging Primer by Charles Bracken. The first edition digs into more of the theory-side (which I obviously enjoy), and includes some image processing workflows and understanding of PixInsight and Photoshop. Now in its second edition, which I don't have, the book is likely improved.

Other books I find important would include astronomy-specific (non-imaging) types of texts, which tend to never go out of date. For example, Kepple and Sanner's Night Sky Observer's Guide details just about any object in the night sky within its three volumes. And don't forget the numerous star charts, like Sky Atlas 2000, Herald-Bobroff Astroatlas, and Uranometria that can help you plan both astronomy observations and astro-images.

As far as magazines, Astronomy and Sky & Telescope are two of the biggest reasons that many people get involved in astronomy in the first place. They deserve a place in your monthly reading list. Others like Amateur Astronomy Magazine and Astronomy Technology Today, as well as non-American publications like SkyNews and Astronomy Now, serve the same types of information. Monthly star charts, observing list and highlights, equipment reviews, current events, and tutorials are consistent features in all of these magazines. And if nothing else, you need to experience the joy of having an image published in at least one of those magazine's image galleries!

There are many other solid books, even if they are a bit dated, that you need to find, especially for those that want to dig into the theory of digital imaging. I have used the Handbook of CCD Astronomy by Steve B. Howell for many years as support for some of my published opinions on the technical aspects of the hobby. Richard Berry's The Handbook of Astronomical Image Processing is a deep foray into the technical side as well, albeit a little dated. Many texts by Michael Covington belong on your bookshelf, if only to make you look like the cool kid, but in particular he has an excellent text called Digital SLR Astrophotography that is well worth your time.

There are two classic books on astronomy optics that should be considered. Star Testing Astronomical Telescopes by Harold Suiter and Telescope Optics by Rutten & van Venrooij will each have you understanding more about choosing proper optics, how they work with a camera, and in troubleshooting optical aberrations in your images.

My friend, Dr. Greg Parker, wrote Making Beautiful Deep-Sky Images more than a decade ago now. I have always appreciated the concise and straight-forward layout of the text. Part of the Patrick Moore Practical Astronomy Series by Springer Press, Parker's book serves as an excellent survey of the hobby from equipment purchase to the published image. A similar text, but more up-to-date, would be The Deep-Sky Imaging Primer by Charles Bracken. The first edition digs into more of the theory-side (which I obviously enjoy), and includes some image processing workflows and understanding of PixInsight and Photoshop. Now in its second edition, which I don't have, the book is likely improved.

Other books I find important would include astronomy-specific (non-imaging) types of texts, which tend to never go out of date. For example, Kepple and Sanner's Night Sky Observer's Guide details just about any object in the night sky within its three volumes. And don't forget the numerous star charts, like Sky Atlas 2000, Herald-Bobroff Astroatlas, and Uranometria that can help you plan both astronomy observations and astro-images.

As far as magazines, Astronomy and Sky & Telescope are two of the biggest reasons that many people get involved in astronomy in the first place. They deserve a place in your monthly reading list. Others like Amateur Astronomy Magazine and Astronomy Technology Today, as well as non-American publications like SkyNews and Astronomy Now, serve the same types of information. Monthly star charts, observing list and highlights, equipment reviews, current events, and tutorials are consistent features in all of these magazines. And if nothing else, you need to experience the joy of having an image published in at least one of those magazine's image galleries!

Comanche Springs Astronomy Campus (CSAC) is the home of over 3500 acres designated by the Three Rivers Foundation for public science education. It is home of several observatories, with classrooms and bunkhouses that can accommodate groups up to 150 or so. Owner of the largest private collection of Obsession dobs, including a 30" on campus, CSAC hosts routine astronomy and astroimaging workshops. Unique is the ability to use actual equipment from Bortle Class 2 skies WHILE learning imaging in a workshop setting. Very special and unique. See www.3rf.org for information on future opportunities.

Comanche Springs Astronomy Campus (CSAC) is the home of over 3500 acres designated by the Three Rivers Foundation for public science education. It is home of several observatories, with classrooms and bunkhouses that can accommodate groups up to 150 or so. Owner of the largest private collection of Obsession dobs, including a 30" on campus, CSAC hosts routine astronomy and astroimaging workshops. Unique is the ability to use actual equipment from Bortle Class 2 skies WHILE learning imaging in a workshop setting. Very special and unique. See www.3rf.org for information on future opportunities.

Workshops, Conventions, and Clubs

Some of the best learning happens when you attend local, regional, or national imaging workshops and conventions. It's as close as you might get to attending an actual imaging "school." Most such workshops will be 3 to 5 days long, with an agenda of topics each day. Depending on the event, the presentations could be wide ranging, for beginners to experts, covering a plethora of diverse areas of interest. This is especially true in the two major national conferences here in the states...the Astronomical Imaging Conference (AIC) held each November in San Jose, California and the NorthEast AstroImaging Conference (NEAIC) held each April in Suffern, New York. The latter conference is a part of a larger exposition known as the NorthEast Astronomy Forum (NEAF) which is the largest collection of amateur astronomy gear you will ever see in any one place.

At the regional level, there are a variety of choices here, which typically includes experts traveling around the country within a reasonable drive from you. One of the most highly recommended is that of Warren Keller's (IP4AP) three day work shop for PixInsight. Warren, author of the book recommended previously, is a terrific teacher and his 3-day introductory workshop over PixInsight is money well spent. As you might gather, the regional workshops can be a little more focused in terms of learning content. In Warren's workshop (which he conducts with Ron Brecher), you will receive hands-on skill-building within PixInsight.

At the Three Rivers Foundation, we have been known to host imaging workshops around Texas, many of which probably involves this author. Most often, these are hosted at Comanche Springs Astronomy Campus (CSAC) at left and are always very affordable, fun, day/night workshops where you get both instruction AND practice. Based in an area of Texas known as the "big empty," it's easy to see that 3RF offers a dark sky experience that nobody else can provide.

Finally, most large cities in the states have astronomy clubs. These clubs usually have Special Interest Groups (or SIGS) that meet periodically to focus on specific aspects of astronomy, including astro-imaging. For example, here in the DFW area, a member of the Texas Astronomical Society of Dallas can attend a monthly astro-imaging SIG at a local library, where there are presentations, processing demonstrations/practice, and open question times. Being in the club also keeps you connected with events that you might not have known about otherwise. You should also remember that anything you do in astronomy can benefit your imaging as well, so be sure to plug into the club as an amateur observer too.

But I think, most importantly, workshops and astronomy clubs offer an opportunity to socially network (non-virtually) with other like minded, motivated astrophotographers and astronomers. These relationships can form the basis for future partnerships, mentorships, and other opportunities you would never have if you remained invisible. At some point, such contacts can lead to your own chance to speak at conventions, make money from the hobby, and even rub elbows with some of your astro-imaging heroes.

Some of the best learning happens when you attend local, regional, or national imaging workshops and conventions. It's as close as you might get to attending an actual imaging "school." Most such workshops will be 3 to 5 days long, with an agenda of topics each day. Depending on the event, the presentations could be wide ranging, for beginners to experts, covering a plethora of diverse areas of interest. This is especially true in the two major national conferences here in the states...the Astronomical Imaging Conference (AIC) held each November in San Jose, California and the NorthEast AstroImaging Conference (NEAIC) held each April in Suffern, New York. The latter conference is a part of a larger exposition known as the NorthEast Astronomy Forum (NEAF) which is the largest collection of amateur astronomy gear you will ever see in any one place.

At the regional level, there are a variety of choices here, which typically includes experts traveling around the country within a reasonable drive from you. One of the most highly recommended is that of Warren Keller's (IP4AP) three day work shop for PixInsight. Warren, author of the book recommended previously, is a terrific teacher and his 3-day introductory workshop over PixInsight is money well spent. As you might gather, the regional workshops can be a little more focused in terms of learning content. In Warren's workshop (which he conducts with Ron Brecher), you will receive hands-on skill-building within PixInsight.

At the Three Rivers Foundation, we have been known to host imaging workshops around Texas, many of which probably involves this author. Most often, these are hosted at Comanche Springs Astronomy Campus (CSAC) at left and are always very affordable, fun, day/night workshops where you get both instruction AND practice. Based in an area of Texas known as the "big empty," it's easy to see that 3RF offers a dark sky experience that nobody else can provide.

Finally, most large cities in the states have astronomy clubs. These clubs usually have Special Interest Groups (or SIGS) that meet periodically to focus on specific aspects of astronomy, including astro-imaging. For example, here in the DFW area, a member of the Texas Astronomical Society of Dallas can attend a monthly astro-imaging SIG at a local library, where there are presentations, processing demonstrations/practice, and open question times. Being in the club also keeps you connected with events that you might not have known about otherwise. You should also remember that anything you do in astronomy can benefit your imaging as well, so be sure to plug into the club as an amateur observer too.

But I think, most importantly, workshops and astronomy clubs offer an opportunity to socially network (non-virtually) with other like minded, motivated astrophotographers and astronomers. These relationships can form the basis for future partnerships, mentorships, and other opportunities you would never have if you remained invisible. At some point, such contacts can lead to your own chance to speak at conventions, make money from the hobby, and even rub elbows with some of your astro-imaging heroes.

|

Online Forums/Social Media

One of the very best parts of the early internet was the concept of a "bulletin board" or "user group." The first true social media, people could gather virtually to ask questions and discuss a variety of aspects of over the hobby or hobbies. Today, remnants of many still exist, such as the Yahoo Groups, which still serves as an excellent place to get user support over a variety of legacy (and current) equipment makes. Once the "web" fully developed, internet "forums" began to take over, yielding a better user experience and interface, with features often including chat and private messaging, and greater participation. Cloudy Nights is likely the best known of these running today, but there are several others like Ice in Space and Astromart that provide similar online communities. As with any community, it's a good chance ask a question, which inevitably yields no end to responses, ranging from the ridiculous to the extremely helpful. More than that, it gives you the chance to search through archives of previous "threads," to see your question has already been answered. Or, it gives you the chance to post an image to get feedback. The biggest issue I have with internet forums is the extreme noise level, where you will have to filter through the blow-hards and phonies and egos, as well as dealing with the inevitable "Mr.-Did-You-Search-First-Before-Asking-Us Guy." I always found it amusing the number of people on Cloudy Nights who are members of the "community," yet aren't willing to give personalized and customized help for those in need. The other alternative to the community forum is via Facebook or Facebook-related groups. Personally, I've enjoyed accepting friend requests from thousands of astronomers and astrophotographers, and then watching them post images, opinions, and questions that pop up in my "news feed." As with any social media, the noise level can be extremely high when dealing with those opining about politics and religion, but a well administrated, astronomy-specific Facebook group can be a joy to use. Just watch out for NASA-bashers and flat-earth conspiracists! |

Conversation heard frequently |

If you want to process some data online, head over to Jim Misti's FITS site. Here are the results of his M8 data processed by 16 distinct hobbyists. It's nice to be able to process the data yourself and see how YOU compare!

If you want to process some data online, head over to Jim Misti's FITS site. Here are the results of his M8 data processed by 16 distinct hobbyists. It's nice to be able to process the data yourself and see how YOU compare!

Data Repositories

You can learn to process astronomical images without taking a single image yourself. This is possible because many people upload their own raw data (or master frames) to the Internet for ANYBODY to play with. Unbelievably, you can even download Hubble Space Telescope data to practice on. Googling "HST public data" or "Hubble Legacy Archive" will get you started. Digitized Sky Survey (DSS) data? Yes, that too. Even data from the James Webb Telescope can be downloaded and processed. The Space Telescope Institute provides such access to an enormous amount of real telescope data.

One of my favorite amateur repositories has been provided by Jim Misti, who uploaded FITS data from a 32" Ritchey-Chrietien scope, as well as 4" apochromatic refractor data. He even uploads your processed results to a page where you can compare it against others who did the same object. It's amazing to see the differences in results among participants, even among some really talented amateur astrophotographers.

Somewhat conversely, it's good to make use of those around us to process our data for us, if only to compare their results with our own. It's an excellent way to understand what is the limiting factor in your images...is it your processing...or is it just the data? Getting buddy-buddy with some experienced and proven astronomy "forum-ites" or making a Facebook request is a good way to find people willing to do it; many of them are probably looking for something to do anyway since they just bought new equipment and will be socked in by clouds. It's called the "equipment curse" and you should definitely take advantage of other people's misfortunes.

Mentors/Consultants

I have stressed the importance of mentoring when it comes to accelerating the learning curve in the hobby. Traditionally, those who are learning the hobby would bounce questions and ideas off of each other, usually online, in an attempt to improve together. But at this point in time, there are many people who have made themselves available as private teachers to serve your needs. Some advertise these services online via their webpages or will let you know they provide such services at various workshops, conventions, or meetings where you might encounter them at a vendor's table.