Total Lunar Eclipse - January 20 & 21, 2019

Location: Grapevine, Texas

Telescope: 6" Takahashi TOA-150 apochromatic refractor

Camera: Nikon D810A

Mount: Takahashi NJP Temma 2

Exposure Info: A series of 700+ exposures taken every 30 seconds. Camera was in program mode, so exposures were automatically bracketed according to lunar brightness. Length of exposures ranged from 1/1000 second to 6 seconds. All at ISO 100.

Telescope: 6" Takahashi TOA-150 apochromatic refractor

Camera: Nikon D810A

Mount: Takahashi NJP Temma 2

Exposure Info: A series of 700+ exposures taken every 30 seconds. Camera was in program mode, so exposures were automatically bracketed according to lunar brightness. Length of exposures ranged from 1/1000 second to 6 seconds. All at ISO 100.

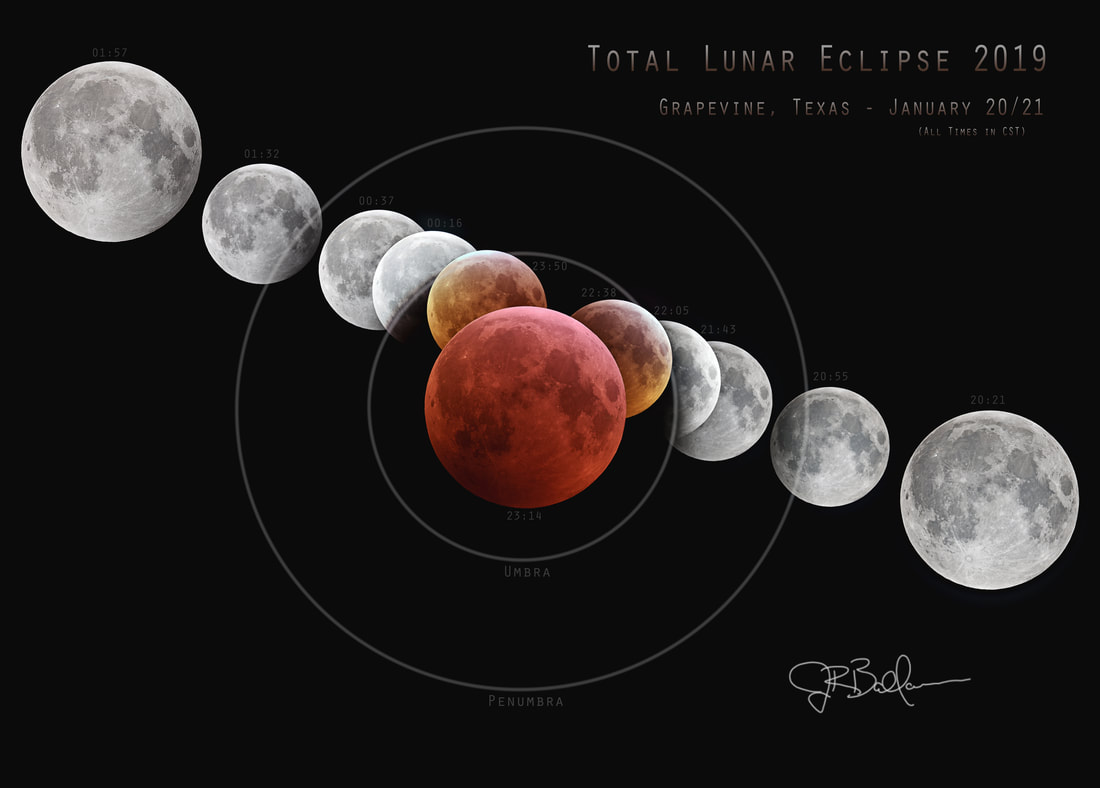

About this Image: This linear composition shows the eclipse sequence, moving right to left. This seems counterintuitive...while the moon moves left to right (east to west) from our perspective in Texas, the shadow of the earth actually catches up to the moon from the left side, eclipses it, and exits out of the moon after about 6 hours, speeding on ahead.

What many do not realize is that there are two aspects to the shadow, a penumbra, where sunlight begins to hide the lunar surface (note the dimming of the lunar limb once it enters the penumbral ring), and an umbra, when sunlight is completely blocked on the lunar surface.

Both the penumbral and umbral rings are shown here to scale. The actual lunar size of approximately 30 arc minutes is demonstrated by the smaller lunar images shown here.

To become a "total" eclipse, the moon must enter the umbral ring entirely. When it does, it takes on a red hue, caused by the scattering of blue light through earth's own atmosphere. In other words, as light passes around the earth and is refracted toward the moon, the absence of the blue light causes the "blood" color, as the Internet likes to sensationalize it. For those wondering why earth sunsets are red, it happens for the same reason described here.

Some lunar eclipse "totalities" last longer than others. Here in Grapevine, Texas, the moon barely entered the umbral ring, which is why even at totality (blown up and centered in this composition) the northern rim of the moon has a slight brightening to it.

Want a good way to know where the moon is during its eclipse cycle? If the moon is dimming, yet you can still trace the entire perimeter of the lunar disk, then it has not yet entered the umbral ring. When it does, it will look like chunk has been taken out of it!

What many do not realize is that there are two aspects to the shadow, a penumbra, where sunlight begins to hide the lunar surface (note the dimming of the lunar limb once it enters the penumbral ring), and an umbra, when sunlight is completely blocked on the lunar surface.

Both the penumbral and umbral rings are shown here to scale. The actual lunar size of approximately 30 arc minutes is demonstrated by the smaller lunar images shown here.

To become a "total" eclipse, the moon must enter the umbral ring entirely. When it does, it takes on a red hue, caused by the scattering of blue light through earth's own atmosphere. In other words, as light passes around the earth and is refracted toward the moon, the absence of the blue light causes the "blood" color, as the Internet likes to sensationalize it. For those wondering why earth sunsets are red, it happens for the same reason described here.

Some lunar eclipse "totalities" last longer than others. Here in Grapevine, Texas, the moon barely entered the umbral ring, which is why even at totality (blown up and centered in this composition) the northern rim of the moon has a slight brightening to it.

Want a good way to know where the moon is during its eclipse cycle? If the moon is dimming, yet you can still trace the entire perimeter of the lunar disk, then it has not yet entered the umbral ring. When it does, it will look like chunk has been taken out of it!